Special Issue 2025 of Apprendre + Agir

Lena Sarrut

Nicole El Massioui

Bernadette Buisson

Alexia Stathopoulos

Abstract

This article, co-authored by four members of the non-profit Lire C’est Vivre, describes and analyzes the work carried out by this non-profit organization within the Fleury-Mérogis Penitentiary Center, the largest prison in Europe, which is located in the southern suburbs of Paris, France. We first present the many libraries managed by the association, emphasizing their role as a possible place of transformation. In order to achieve this goal, a rich and varied cultural programme is set up. We have specifically targeted three cultural actions that we will present in detail: the weekly reading circles, the Goncourt Prize for prisoners and an introductory workshop to sociology. Finally, we return to the professional training leading to a diploma for inmate librarians and its importance in relation to the non-profit’s desire to provide library services as close as possible to public libraries.

Keywords: prison libraries, reading, literary prize, cultural actions, vocational training, links, common

Introduction

This article presents some of the actions implemented by a French non-profit (law 1901)1 called “Lire C’est Vivre” (LCV). LCV was created in 1987 by professional librarians who went to the Fleury-Mérogis prison, the largest in Europe, to take care of the libraries on Mondays on their day of rest (which says a lot about their commitment to the cause).

We write with four voices, as members of this non-profit: one employee and three volunteers. Nicole has been a volunteer for four years. A retired researcher, she leads a reading circle in a facility for men and another in a facility for women. Bernadette has been a volunteer for five years. A retired pediatrician, she leads the circle of a men’s facility and the Goncourt Prize for Prisoners. Alexia has been a volunteer for two years. An independent researcher in sociology, she leads an introductory workshop on sociology in a men’s facility. Lena was the director of Lire C’est Vivre. She worked for the non-profit for more than seven years. She is currently working on a doctoral thesis on the written and drawn expression of detainees. She is the voice of the non-profit’s salaried team.

As we speak with several voices, we will let you know, when necessary, which of us is speaking. We also choose to write in an inclusive way or by agreement of numbers when it is more representative.2

Our aim is to show the role of prison libraries, supported by the current law in France,3 and which we promote, as library professionals and committed volunteers. For us, libraries are a key resource for people who are in prison. We will show that libraries allow encounters, and they are spaces for debate, in an environment where this is usually forbidden (at least, in the case of the French prison environment). We hope that this article can inspire others as much as it did the four of us.

We will first describe prison libraries as they are managed by Lire C’est Vivre, within the Fleury-Mérogis Penitentiary Center (CPFM). Then, we will present in detail three cultural actions, part of a broad cultural programme that we are developing: the weekly reading circles, the real backbone of LCV’s activity; the establishment of the “Goncourt des détenus” literary prize, a national initiative on French territory; and an introductory workshop in sociology, which aims to allow detainees to “research the research system in which they are bound […]” (Nicolas-Le Strat, 2024). Finally, we will discuss professional training for the title of library assistant and the way in which we support prisoners who become library assistants. In this section, we will show the importance of theoretical training, allowing auxiliaries to carry out their work in the most professional way possible and take an interest in contemporary library issues while adapting to the prison environment. The auxiliaries help to make libraries dynamic and attractive. They are essential for the proper functioning of libraries and the activities that take place there. The professional activities and training that we present form a comprehensive and coherent policy of public reading in prisons.

The Library as a Resource

The Fleury-Mérogis Prison (CPFM) consists of a remand prison and a detention centre.4 We will focus here on the presentation of the former, as the detention centre is not functional at the time of writing (spring 2025).5 The Fleury-Mérogis prison (MAFM) is made up of five buildings for men including specialized sections such as the juvenile unit (QM), the isolation unit (D3IS or QS) or the disciplinary unit (QD): the men’s prison (MAH); and a building for women: the women’s prison (MAF). Each of these buildings (or districts) has a library.

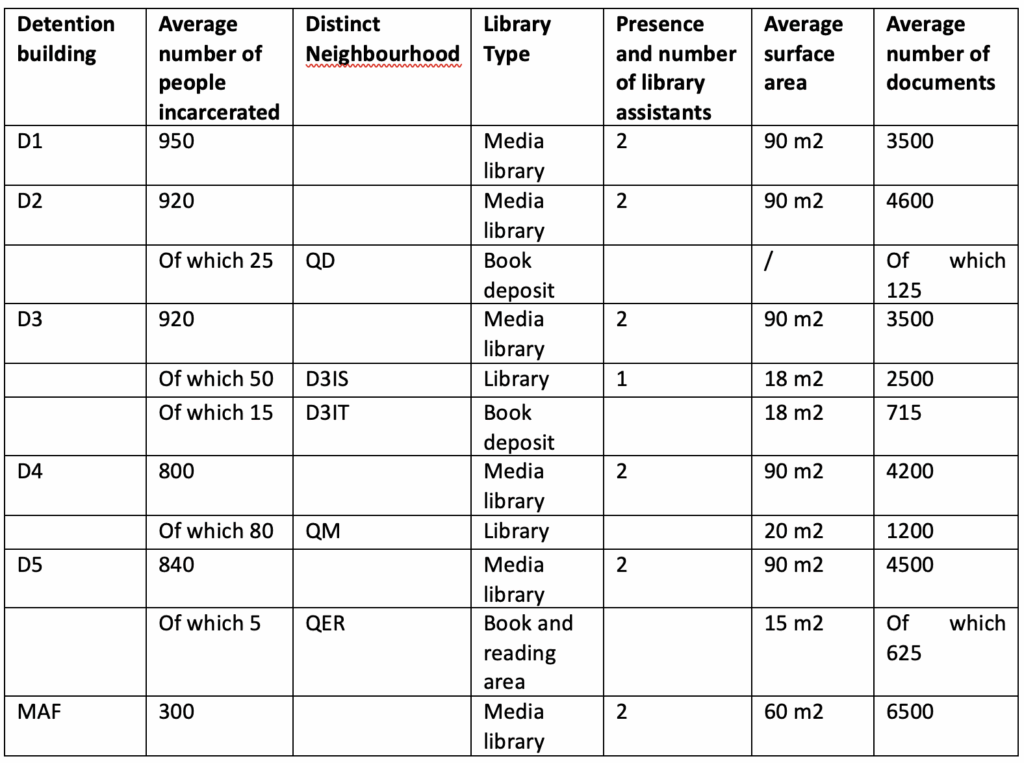

The MAFM has about 4500 inmates, spread across these different buildings, in which we must guarantee direct access to books. There are therefore nine media libraries distributed as follows:6

- Within the D1 building, there is a media library on the ground floor. It is accessible to inmates on the four floors;

- In building D2, the media library on the ground floor is accessible by inmates on the first three floors, the fourth being the disciplinary section which has a “reading point”;

- In building D3, there are two media libraries. The one on the ground floor is accessible to inmates on the first three floors. On the fourth and last floor is a solitary confinement (for safety) and total isolation ward. A small library is accessible for one of the two wings, with direct access. The second wing has a book depository;

- In building D4, there are two media libraries, one for adults, the other for minors. The adults are placed on the first, second and fourth floors and the media library is still on the ground floor. The minors’ library is on the third floor;

- In building D5, there is a media library and a reading area. The first one serves inmates on the first three floors, while the second serves the top floor where there is a radicalization assessment unit;

- The women’s prison has a media library that welcomes adults and minors (at different times), as well as several book deposits, in particular in the isolation and disciplinary section and in the “nursery,” a section that welcomes pregnant women and mothers detained with their children up to the age of 18 months.

The libraries cover the entire prison and the people under the prison administration’s jurisdiction.

In each of the media libraries, two inmate librarians work five days a week, from Monday to Saturday, with Thursdays being devoted to professional training (which we detail in the second part of the article). Each building accommodates a different type of penal population (sentenced to more than 24 months in D1, remand in D2, sentenced to less than 24 months in D3 and D4, etc.) and this greatly influences the operation of media libraries, as does the recruitment and training of inmate librarians who will remain in their posts for a relatively long time depending on their judicial situation. All these parameters must be considered when it comes to offering activities, workshops, or any other action within the libraries. This is also the reason why I [Lena] am now exposing them to you.

Generally, the prison library, through its function and space, and in keeping with the principle of normalcy, has been found to give inmates a level of freedom that essentially catalyses responsible, self-directed and critical decision-making skills. That is to say, in having the freedom to choose to use the library services and select the books they read, inmates experience an appreciation of their own self. The prison library reminds them that there are still aspects of their lives over which they have control. (Krolak, 2020: 14)

The library is a place out of time, a place of refuge, a place in which prisoners regain a certain control over their own decisions, by choosing the books they bring back to their cells, for example. It also gives them collective power outside of the relationships and/or tensions that are played out during the walks outside.7 These are the areas that we are working on in particular, by offering books on all disciplines and fields, accessible to all. To make the places even more dynamic, we also offer a broad and varied cultural programme. In the following lines, we present some of these initiatives, distinguishing them into two main categories: cultural activities and vocational training.

Cultural Activities

The Reading Circle: Reading Aloud as a Vector of Collective Action

The reading circles were developed in 1987 by professional librarians from the Essonne department, in the south of the Paris region, where the prison is located. Unlike a book club, where people discuss books they have read individually, these circles bring together people who read aloud, in turn, and where each participant has his or her own copy of the book. This original system has remained operational ever since. The volunteers who lead these circles come from different backgrounds, each with their own life background, professional achievements, experience, and literary preferences. Bernadette, a retired pediatrician, and I [Nicole], a retired researcher, are good examples of this diversity. Our general motivations are the desire to share, to discover authors and books, and to provoke debates around the themes of the books we choose, informed by the group of participants we read with.

The Participants: Who Are They?

The inmates who participate in the reading circles, whom we call participants, are of all ages. There is no typical profile in this population. Some are avid readers, have studied for a long time, others are not, and many have failed at school or have, at least, developed an aversion to the school system. Some allophones come to listen, follow the reading and read a few sentences. This is the case for Mourad8 who started attending the reading circle without knowing how to read French. In just a few weeks, he progressed and was able to read aloud more easily, with pleasure and also with pride! Another participant, Mohamed, signed up to be part of the jury for the Goncourt Prize for Prisoners and, since he could obtain a leave of absence, went to the national deliberation to defend the book chosen by the group. The participants usually attend these circles on a regular basis.

How Circles Work

The circles are made up of a maximum of 17 inmates, including the two library assistants, and are led by one or two volunteers. This limit is set and enforced by the prison administration. Circles meet once a week in the prison libraries and last from two to three hours. The book is first presented, as well as its author, the literary setting, the characters, and possibly the historical context of the author and the book. Each participant (including the facilitator) has a copy of the book for the duration of the circle and reads, in turn, regardless of their reading level. Inmates, like volunteers, can stop reading at any time for clarification, definitions, or discussions about what has just been read.

The readings are varied, in French or translations of foreign literature, classic or contemporary, novels, short stories, play, poetry and, almost always, fiction. For example, this year in the D1 building, where I lead the reading circle with Bernadette, we discussed the work of Albert Camus through his latest book The First Man, then The Stranger. Then, an actor came to present The Myth of Sisyphus, as revisited by Albert Camus and which evokes a man condemned to an endless task, a perpetual toil that seems absurd. However, Albert Camus invites us to imagine a happy Sisyphus, finding meaning in the effort itself. These works have sparked many debates on childhood memories, relationships with father and mother, but also on lost countries and life challenges. At the MAF, where I lead the reading circle with another volunteer, we organized a cycle around the French author, Colette. Over the course of a few weeks, we read several books written by her, then we brought in a speaker for a general presentation of Colette’s work and her contribution and place in the cultural context of her time. The participants enjoyed the readings of plays, which allowed them to appropriate a character (we distribute the roles at the beginning of the session) and to “play” him or her throughout the reading. We also read Art by Yasmina Reza and Twelve Angry Men by Réginald Roze.

Reading aloud is a technique recognized for its benefits on text comprehension (Reyzabal, 1994), word memorization, and attention level (Dehaene, 2007) (Lachaux, 2020). This method allows the group to be in an attentional and often emotional symbiosis during the reading, feeling safe in the protected place that the library represents. This time of sharing is exceptional, and it is particularly important in the restricted and constrained environment of prison.

This group reading device also promotes the possibility of something happening. During an exceptional session that we [Nicole and Lena] led, in order to get feedback from the participants on the actions carried out by the non-profit (the circles, of course, but also the cinema-debate sessions, the writing or comic book workshops, or the Goncourt Prize for prisoners), the participants expressed their perceptions and feelings: the astonishment of the encounter with readings, ideas, the reactivation of a memory, the short moments they forget they are in prison, encounters with a character they have recognized themselves in, internal sensations that they have shared, which are accompanied, contained by the group and allow them to feel calm, a feeling of well-being, which is exchanged and shared by and with the group.

The following testimonies are taken from the documentary film Entre les barreaux les mots, directed in 2017 by Pauline Pelsy-Johann and co-produced by Lire C’est Vivre. In particular, they bear witness to the contribution of reading circles [translated from French by the editors]:

[…] At the beginning of the reading circle, we were all very shy, very reserved; We were all ashamed to express ourselves; we had prejudices, and the act of reading aloud was like a key, the act of being able to read something, to be able to express ourselves… It’s an expression that we’re not used to in prison, we don’t have the freedom to speak, to express ourselves. At the reading circle, talking, reading a book, it’s something … and when you go back to your cell, you have peace, you feel so good that you felt alive, in fact.

Here, in prison, it’s always the same stories; we have emotions that we don’t know, that we’re not used to experiencing. In a book, we can find them, find certain emotions; it gives us back our existence, it makes us live again what we have lost. I can have a little sadness, joy… These are emotions that I had on the outside and I find them in books.

In the programme, broadcast on the French national television channel “C à vous,” a short series was devoted to reading in the Fleury-Mérogis prison. A participant, interviewed for one of the show’s columns, testifies in turn: “Reading soothes me, it gives me a lot of strength.”9

These beneficial effects of reading circles can be enhanced when we have the opportunity to invite the authors of the books we read. The participants prepare for this moment with the volunteers. They think about their questions and feelings about the work. These meetings, allowing a concrete contact with the writer, are generally very much appreciated. They are also very rewarding for the participants, who are impressed and touched that writers come to meet them in their place of incarceration.

Book Volunteers, Mediators: What Posture?

Volunteers who apply to come and lead reading circles are first received at the non-profit’s office and interviewed by its director in order to know the person and understand their motivations. Then, for several weeks, these new volunteers are accompanied to the reading circles of the various buildings to familiarize themselves with the functioning of the prison and the circles. If all goes well, they become members of a pair of leaders for a particular circle. Some applicants, once confronted with the prison environment, do not feel capable of continuing in this environment and turn to other non-profits.

One of the difficulties in leading the circles is the choice of books. The important thing is to know how to adapt to the group, not so much to its level of reading capacity, as to its level of attention and possible investment in the “imaginary” world that an author embodies. In very concrete terms, attentional fluctuations increase particularly as the end-of-year celebrations approach, a period that is always difficult, especially in the event of social isolation. This is also the case as the summer holidays approach, when participants know that there will be fewer activities and therefore more solitude over a period of two months. Similarly, it is important to discuss the choice of books within the pair of facilitators in order to avoid the biases that each person may have (political, philosophical, gender bias, etc.). This is why having two volunteers for each circle allows a certain balance that maintains a broad approach adapted to each circle. Volunteers should also be able to adapt to what is happening in the outside world, in France or elsewhere. It is sometimes essential to let the participants “debrief” external events (such as when there are elections in France or in other countries) at the beginning of the session in order to start reading more serenely. We have already chosen a book or an author according to current events. This was the case when we read Missak by Didier Daneinckx, in reference to the pantheonization of Missak Manouchian, in recognition of the involvement of foreigners the French Resistance during the Second World War.

It should also be mentioned that the inmates are very grateful (and express it very frequently) for the work and availability of the circle leaders. The simple act of coming, preparing the sessions and listening to them touches them deeply and seems to bring them comfort. As Gérard said to me the other day, “I’m looking forward to Monday and the reading circle with great impatience; I’m happy to see you and I feel better afterwards.”

For me [Bernadette], it is the meeting with the other volunteer (one’s partner) and with all the members of the Lire C’est Vivre non-profit that is decisive to keep recruits in the project in the long term. You must like reading, of course, but it’s also a choice that goes beyond wanting to do a voluntary activity. This activity resonates with our history and identity. When we lead the reading circles, we are not educators, purveyors of knowledge to be dispensed. We are present in the library according to a fixed time slot with our own knowledge and sensibilities and, especially, with texts. We then become “transmitters” of a possibility of encounter with an “other” universe. It is almost enough to be there at the right time, with the right text, for it to become a bearer of openness and possibly a revelation of creativity. On the subject of Joseph Conrad’s Youth, for example, I had noted a few spontaneous sentences from the group of participants in the D1 circle (men’s building) who evoke this opening: “It’s a metaphor for life”; or “In a few words, we dive into it.”

The Goncourt Prize for Prisoners: Where One Learns to Debate, to Argue, and to Socialize

The Prix Goncourt is the most prestigious and one of the oldest literary prizes in the French language. It has been awarded annually since 1903. Long before the Goncourt Prize for prisoners, several versions of the Goncourt have been created: Goncourt for high school students (since 1988), Goncourt international (such as the Goncourt du Canada, the latest addition in 2023). In France, in 2022, reading was declared a major national cause. Under the impetus of the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Justice, supported by the National Book Centre and the prison administration in conjunction with the Académie Goncourt, the Goncourt Prize for Prisoners was created. Its objective is to strengthen the prison population’s access to reading, which is considered a vector of social inclusion and reintegration.10

Unfortunately, the initiative only reaches a small part of the prison population11: in Fleury, this was particularly striking because most of the volunteers for this action were participants from reading circles, people we already knew and on whom we could a priori count, thus allowing the success of this large-scale action. Indeed, as for the reading circles, a limit imposed by the administration constrains the number of detainees to 20. At the national level for the year 2024, 45 establishments participated, including the Fleury-Mérogis prison, i.e., about a quarter of French prisons (including the overseas departments). Nearly six hundred people participated, which represents less than 1% of the prison population. The structures carrying out projects are the cultural non-profits (and associative libraries like ours), the cultural service or the educational service (the National Education) which join forces to carry out the action. We have integrated the prize into our annual cultural programme, promoting collective action based on listening, as with reading circles, and on critical thinking. However, unlike the reading circle, the weekly meetings are debate sessions.

The Jury of Fleury-Mérogis

For the third edition of the Goncourt Prize for Prisoners, in 2024, we formed a mixed group of about 20 people, putting together women and men from building D1 and building D2. Usually distributed within the buildings according to their criminal profile, the volunteers are grouped together despite very varied profiles (convicted for more or less long sentences, remanded, correctional or criminal)12 thanks to the support of the prison (which allows and organizes the transport of participants from one building to another) and the excellent reputation of the Goncourt Prize. Once the group is formed, it becomes a jury, and the volunteers and participants are designed as “jurors.”

Sixteen books were selected for this edition. The list of books is the same as that of the Prix Goncourt. Four selection lots are distributed by the ministries to each project leader. Books are ordered as soon as the selection is announced, usually at the beginning of September. The ten interregional deliberations take place in the second half of November, and the national deliberation takes place in mid-December. The vote behind closed doors is immediately followed by the proclamation of the prize, in the presence of the Ministers of Culture and Justice. The Goncourt Prize for Prisoners then closes the season of prizes for the literary season.

The Hourglass Is Turned Over!

In Fleury-Mérogis, time starts running out as soon as the books are received. At this stage, the group is usually already constituted and the jury list approved by the officers in charge and by the central prison administration. The latter authorizes or refuses the meeting between the different criminal profiles of the selected people and makes sure no one on the jury is banned from being in contact with other members. Those who register commit to participating in the weekly meetings and to reading as many books as possible over the period. While some of them are already familiar with reading, for “lighter readers,” it is a real challenge. Sometimes, the first session takes place before all the books get here. Some books may be out of stock following the announcement of their selection in one or more literary prizes. In this contact, the first session is used to present the prize and the activity in broad strokes. What is the history of this award and how does it work? What are the deadlines? It is also useful for creating cohesion within the group. The posture of the volunteers who lead the sessions is also essential to generate cohesion and emulation. Unlike reading circles, where a pair of volunteers lead the discussions, the prize sessions are led by a small group of volunteers, in alternance. Some sessions can be held by two, three, or four volunteers in order to recreate smaller groups and encourage fruitful exchanges in the jury.

After this, a session is held every week, starting at the end of September until the final result. However, the group must select three titles, about a week before the interregional deliberation. Therefore, participants barely have two months to take turns reading each of the sixteen books, each available in four copies. From the second session, the jurors comment on their first readings and exchange their points of view, sometimes with strong contrasts. This was notably the case for Abdellah Taïa’s Le Bastion des larmes, which was initially strongly criticized because of its theme,13 but the book has continued to be positively re-evaluated. “There were lots of possible stories, he [the author] didn’t know how to take advantage of them,” “the sentences have no more than 5 words,” then “it’s overwhelming,” “a nice surprise, he dares to say how it works,” “it’s a beautiful love story.”14 For the book La vie meilleure by Étienne Kern, I [Bernadette] observed the opposite: “It’s very well written, poetic even, he [the author] transmits something to the world,” “he instills happiness,” “he invents with joy and makes life better,” then a reversal: “yes, but he [the character] is always sad, melancholic and his wife is unhappy,” “It’s not an interesting book, I’d like to rewrite it,” “Is he a genius or a charlatan?”

After six to eight weeks of debate, two jurors are chosen to represent the group. A request is made to the Commission for the Execution of Sentences to obtain permission to attend the interregional deliberation day. At this point, a collective preparation begins. These two representatives must carry out the voice of the group and the results of their deliberation. Their role is to defend the titles selected by the group and lead them to the final deliberation.

For the jurors, the reading activity is intense, from September to the end of November. The dynamic process, the emulation and the pleasure of being together all stimulate their desire to read. One of the participants even said during a television interview that she chose to “skip the walk” to finish reading the sixteen titles, because she had set herself the goal of reading the entire selection. Other jurors told us that “even on the walk,” they continue their exchanges and debates. They lose themselves reading, often surprised when they realize they read an entire book in a few days, or when they cannot put it down and finish it in less than 24 hours!

A Commitment and a Collective Dialogue

This prestige of being a juror, we are all honoured!15

The participants take on a responsibility: they are no longer reduced to their prison number; they feel recognized and are honored by it. They express their feelings in strong words: “It’s a responsibility, it changes our condition as prisoners, we are no longer a prison number, a prisoner, we are a person who has to give an opinion on a book.”16 Their opinion is considered. They think of themselves as partners and no longer as outcasts. Just like us, in the first year, the group wondered what impact the award would have in the general public. They were surprised by the media coverage and delighted to realize the chosen book would clearly be identified as the recipient of the Prisoners’ Goncourt, like any other literary prize.

Every week, they wait for this meeting, in a group of men and women.17 They express their perception of the beauty and emotion that reading brings them. Here are a few words from the notes I [Bernadette] take during the sessions: “an emotional shock,” “I feel choked up,” “chills,” “I was overwhelmed,” “the next day, I couldn’t read anything else,” “a rare beauty,” “there is beauty in the midst of enormous ugliness,” etc.

We put participants in a situation where they have to read books (and what a responsibility!) that would not necessarily be interesting to them, and (sometimes with great surprise) it is “A great discovery that [they] did not expect.” During the second edition, an avid reader told us, “With Humus by Gaspard Koenig, I got out of my comfort zone.”

Through these exchanges, everyone becomes familiar with the books, guiding the following readings. All it takes is a new opinion, another point of view, to pick up another title that was left aside initially. The transmission between the jurors is horizontal and from session to session, the presentations become more extensive and better argued. As a volunteer and facilitator, I try to intervene as little as possible. Our presence must be conducive to their autonomy. I ask for clarification on certain opinions, or I remain present to facilitate discussions. Thus, the participants become real literary jurors, listening to each other, debating, arguing.

The adventure is therefore collective, both in the cohesion between the volunteers, between the participants, and between volunteers and participants. By walking this part of the road together, we develop each other’s ability to think about each other, and to think about ourselves differently. We share in the act of reading and listening to each other, and we perceive what we have in common. Literary texts allow this encounter with the other. These books become the basis for an open, dynamic conception of our own identity, in opposition to current temptations of self-isolation and opacity (Laplantine, 1999). The jurors thus take the risk of experience, difference, or even dissonance. This is what makes discovering works they might never have read elsewhere so rich.

The Introductory Workshop to Sociology or the Experience of Collective Research: A Facilitator’s Posture

Since February 2024, an introductory workshop to sociology (“socio workshop”) has taken place in the library of building D2 of the men’s prison. The initial proposal was as follows: to accompany the participants in responding to a call for papers launched by Phanères editions on the theme of “prison subjectivity.”18 Twelve men participated in this intramural experiment, following the process of any call for papers, well known to academic researchers. In March 2025, their text was published in the collective work entitled Comment construire une subjectivité carcérale. Un chercheur en prison (Rebout, 2025). The workshop continues to this day, seeking and finding new spaces to share the fruit of his research: a scientific communication at a conference at the University of Lille, in April 2025, and currently, the development of a contribution addressing life in detention (through the metaphor of the “prison chessboard”) and the theme of art in prison.

Lire C’est Vivre, like cultural workers in prison, does not usually offer workshops on prison. Why offer an introductory workshop to sociology in libraries on the theme of “prison subjectivity”? The questions raised by Pascal Nicolas-Le Strat on the possibility of those “actually involved” (Nicolas-Le Strat, 2024) to take up the research processes that concern them particularly echo my [Lena] dual posture of researcher and professional intervening in detention. How can we open up spaces for reflection in detention and on detention? Why give back a part of the “work” to incarcerated people? The work carried out within the sociological workshop is intended to initiate answers to these questions and to promote experiential knowledge, often seen as “minoritary interest?” in the scientific research community.

Participants very quickly questioned their legitimacy, not to doubt their right to take up the question of prison subjectivity, but on the contrary, to claim it. They defined themselves as “inmate-researchers,” thus claiming this role for themselves. However, the group did not operate in total autonomy; they did not self-organize to “make research,” at least not at the beginning. In the following, I [Alexia] reflect on my role as a facilitator of the collective process carried out by the group within the socio workshop.

Why talk about facilitation? Firstly, because the “simple” act of entering detention to offer a workshop […] opens up the possibility, for those interested, of being able to meet regularly in a place conducive to exchanges and reflections, in our case the library. […] Secondly, because we had to experiment with work processes that could support collective reflection and writing, in a context that is by nature restrictive and limiting, without access to the Internet, without a computer, without contact between sessions. In a pragmatic way, I played the role of curator and transmitter of the traces left after each of our ten days of work. Thanks to a recorder, all the exchanges could be preserved for the duration of the workshop. I gradually transcribed them and passed them on to the group so that everyone could keep track of the process and add to it to produce a report together. (Stathopoulos, 2025)

The first workshop allowed us to introduce and “comprehend” (grasp together) the subject. I proposed and led a working session aimed at defining two key words: “subjectivity” and “prison.” Using “post-its” and markers, the members of the collective set about making a kind of mental map appear on the tables, in the centre of the room, making visible the thought process. Questioning, in turn, the meaning of the words, reacting to the proposal of one, completing the answer of another, themes and subthemes quickly emerged, allowing a common approach to the subject. During the following workshops, I was attentive to the passage and distribution of speaking rights, asked questions of comprehension and clarification, organized the schedule of the sessions, supported and accompanied the group in its work, but above all, I observed the participants gradually delve into the world of research.

More than a year after the beginning of the workshop, following a presentation that we [Alexia and Lena] gave for the group at a conference and to answer a question from a researcher in the audience,19 the inmate-researchers question their position as much as mine [Alexia].

[…] It depends on the conditions of detention. Are we rationalizing? You offer us the possibility, with our agreement, to rationalize. So we have to rationalize. I mean that it becomes an imperative because we answer a proposal, and therefore you are obliged to put components down. And I think the framework works because you’re there, in the sense that… I’m quite rigid on these points, maybe it’s the impostor syndrome but using the term “researchers” puts pressure on us. […] And, actually, you’re still there behind to cover us, which means that you still take a snapshot and rationalize for us as well. (R., researcher-inmate participating in the socio-social workshop)20

I defend my position as a facilitator, as a transmitter of research, in particular because I have the possibility of finding opportunities to disseminate the reflections and texts developed in the socio workshop (such as those mentioned above), and to transmit them to the group so that they can take them up if they wish. Thus, through my presence in the library space, I forge a place of debate, of collective creation that the members of the group seize in order to research the other, through itself, and itself, through the other. Presently, they are wondering about other possibilities of disseminating their work, particularly inside the prison.

[…] to go further, the guys who have been researching for a few months could perhaps give a lecture upstairs in the worship room in front of the other inmates , to explain … it could be the next step, to make them think by saying, “We have been thinking for months, this is what came out of it…” (M., researcher-inmate participating in the sociological workshop).21

As a researchers’ collective in detention, questioning the reasons “why” we take a sociological approach, and what to do with it beyond the process that concerns us, means (re) positioning the political and epistemic stakes of a recognition of the experiential knowledge of litigants about the institution that imprisons them. As Gilles Chantraine explains, such an approach “presupposes a rejection of the symbolic hierarchy of discourses that erects one as a ‘true discourse’ and condemns another to invisibility, and thereby introduces a break with the movement by which the traditional history of institutions and penal stigmatization condemn, in the past as in the present, litigants to an intolerable silence” (Chantraine, 2005)22. Documenting, questioning, analyzing, and deconstructing the social mechanisms of the prison system, which constitutes an instrument of power, from within the prison, anchors the socio workshop in a dynamic that is rare in prison settings: the development of a common knowledge from the complex situation of deprivation of liberty. Conducting research from the situated point of view of researcher-inmates is indeed far from being socially, epistemologically, and politically neutral. It is an experience which, if only symbolically, makes it possible to “restore to the person who is the object of the criminal sanction his status as a political subject” (Chantraine, 2005).

Within an institution that encloses a collective while fearing and restricting the possibilities to think and act of this same collective, doing research together makes possible (although still precarious) a process of shared elaboration. Ethnographic, anthropological, and sociological practices are all tools, opportunities, or windows for thinking, analyzing, distancing reality from the centre and the margins of lived and experienced situations, and, concomitantly, shaking them up, (re)drawing them and, perhaps in the long term, transforming them (?)

What to Remember From the Cultural Actions Presented?

In the three cases discussed so far, the position adopted by facilitators is decisive for the success of each session. Indeed, they do not intervene as “knowers”; they are mediators between the object (the book, the Prix Goncourt, and sociology) and the group of participants. Through these concrete examples, we put in question the position of the mediator. The participants are volunteers and, even if they sign up for personal reasons (eg. to get out of the cell, to keep busy, to learn something, to meet others, to traffic, etc.), they are usually present and assiduous and as we have described above, come out after several sessions showing their attachment to the “activity.”

We are committed to highlighting the impact of all these actions on prisoners. In light of statements recently published in the press, which criticized socio-cultural activities and other “recreational activities” in prison,23 it becomes crucial to explain and justify our actions to our partners, and more broadly, to the general public. This is why it seems necessary to us to assess our participants’ satisfaction and to publish the results of these surveys. We also set up meetings where all our volunteers can discuss the difficulties and possible improvements of our actions. Lire C’est Vivre, through its members and its salaried team, develops a rich and varied cultural programme, open to all inmates (without selection criteria other than the limited number of places and the motivation of the participants).24 These activities each have their own objectives, but they are common and, like the three cultural actions presented, they are designed to respect the law providing access to information and culture to the people in the care of the Ministry of Justice.

These actions also aim to develop participants’ knowledge in the broadest sense and to establish or re-establish dialogue as well as debates that allow them to express themselves and confront their ideas with others. Thus, they aim to reactivate social ties and the ability to discuss and affirm one’s ideas clearly and calmly in an environment where the individual is diluted in anonymity (ie. one becomes a prison number) and strict rules. Our hope is that, in addition to the well-being that this can bring incarcerated individuals, all these actions will be beneficial in the long term and contribute to a better adaptation to living conditions in prison, followed by a less harsh rehabilitation to “outside” life.

As the cultural programme it sets up, Lire C’est Vivre recruits and trains incarcerated library assistants. These auxiliaries are in charge of the reception of prisoners in all the libraries. Their presence, required throughout the opening hours of the media library in which they are assigned, is essential to the proper functioning of the premises. They enliven the library, both at the reception and during cultural activities, and maintain the link between the non-profit (volunteers and employees) and the penal population. The next part of the article describes the professional training that the auxiliaries receive while working in the prison libraries.

Library Assistant Training

How to Train Librarians in Prison? And Why Do It?

In France, inmates who work for the prison are called “auxiliaries” and more commonly “auxis.” They can clean indoor or outdoor spaces, prepare or serve meals, distribute “canteen” products (bought in the canteen) or, what interests us here, be librarians. Lire C’est Vivre wrote a mission statement, which could not be called a job description since the inmates were not subject to French labour law. However, in 2022, a prison labour law was introduced, thus improving working conditions, requiring in return a significant adaptation of the prison administration and private companies – in particular for workshops (factories).

The recruiting process for “auxis-bibliothèques” involves two interviews: an interview with the prison work officer or the unpaid activities referent (depending on the buildings), then an interview with the director of our non-profit. The employer is the Prison Administration, but the tasks are carried out under the responsibility of the non-profit. The profiles of the inmates who become library assistants vary, but they have in common that they know nothing about the librarian’s profession (based on a small survey given to volunteers and founding members of the non-profit, there has never been in Fleury-Mérogis, as far as I [Lena] know, an auxi-library who was a librarian before incarceration). Moreover, it rarely happens that library auxis have experience in the cultural sector—I only met a former publisher-printer and two people who worked in the film industry, between 2018 and the beginning of 2025, during which time I was also active in the film industry.

I could mention daily training: when the non-profit’s employees go to libraries and take the time to train library assistants on site, but this exists in many countries and has already been documented (Krolak, 2020). In France, almost twenty years ago, a guide “for inmate-librarians” was published by French entities working with books.25 This guide allowed inmates who were library assistants to learn about the basic elements of the profession. It was particularly valuable in a context where few prison libraries had a professional librarian.

Instead, I would like to present an innovative initiative, which we have been implementing for ten years, a vocational programme that leads to a diploma: the library assistant training provided by the Association des Bibliothécaires de France (ABF). One of the primary objectives of this programme, adapted to the prison world, is to provide meaning to detention. It is no longer a question of having the position of auxi-library like any other position of auxi in detention. Librarian-inmates receive training that leads to a nationally recognized certification. If they leave prison during the programme, they can join a training site anywhere on the French territory to complete it. The programme is open to men and women and provided in a mixed gender setting.26

In order to present this programme in more detail, we will rely on concrete examples of collaborative methodology and therefore on specific classes.

How Does the Vocational training as a Library Assistant Work?

The programme consists of 200 hours of class, a 35-hour internship and a minimum of ten hours of volunteering or salaried work per week, in a library. In agreement with the Association des Bibliothécaires de France (ABF), we have adapted the 35-hour internship, which is impossible to set up in prison, by adding days of classes, two leaves of absence, and a special assignment in place of the internship report. Lire C’est Vivre is responsible for up to eight days of training over the year, setting up special days on specific themes about the library environment. In 2025, for example, we invited a journalist to come and talk about media and information literacy, freedom of press around the world, and the role of mediators (including librarians) of information. A librarian specializing in adolescent literature also came to provide a day of awareness about “Dark Romance,” publishing in this sector, and its target audience.

Classes always take place on Thursdays, from the start of the school year in September until the presentation of the provisional title at the end of June. Libraries are therefore closed every Thursday, since all library assistants on duty are required to be present. The only ones exempted are those who have already taken the training and obtained their diploma the previous year, who have, instead, an additional free day per week.

The training is paid for, thanks to a public contract of the Île-de-France region for vocational training of people placed in the hands of the law.27 The “auxis” become “stagiaires” in vocational training according to the jargon of the region, and “learners” according to the jargon of the ABF. They are constantly named, but never really integrated into this process.

Another administrative complication is to track and assess the trainees’ progress. Indeed, auxis can be appointed to this post at any time of the year and be transferred or released at any time of the year. It therefore happens that a trainee joins the training at the last semester in June, and a trainee can be registered for the start of the school year in September, only to leave after the first semester, forcing us to find a replacement as soon as possible. There are 16 places per cohort, and it is not uncommon for us to have a rotation of 30 to 35 people over a year. However, a small core of three to seven people usually manages to complete almost all the programme and pass the exams. This is one of the main reasons why we consider that this programme provides meaning to detention. It leads, occasionally, to vocations and to professional pursuits, following release from prison, in an environment more or less related to libraries and professions in information science or communication.

Trainers: Professionals Working at the Service of Learners

The ABF trainers28 are professionals who are working or have worked in a library. They come from different sectors: municipal or agglomerative libraries, university libraries, whether networked or not, small municipalities or larger cities (Paris, in particular).29 They have worked in the youth or adult sections, with adolescent audiences, outside the walls, in the music, media and sound sectors or even in cinema or heritage libraries. They are directors or employees, in management or not. They manage budgets of 2000 euros or budgets of several millions. They work in teams of two people, with volunteers or in structures with more than 200 employees. All these experiences, rich and varied, are passed on to the trainees.

Trainers try to get off the beaten track by offering collaborative courses, with participatory methods inspired by popular education or what has been put in place in their organization. The introductory course is led by a librarian with 20 years of experience. It begins by introducing the training and the ABF. The rest of the morning is dedicated to a presentation of each participant. Rather than explaining to them what a library is (or is not, for that matter), she asks them what a library is for them, and then to describe the ideal library in their mind. When they give and confront their answers, it makes them react and debate. It pushes them to go further in their reasoning.

Participation is important for a public generally not inclined to overly “academic” methods. Asking trainees to sit for six hours during the day is a challenge. Movement and participation improve their ability to concentrate, which is often impaired by the noisy, uncertain and uncontrolled daily life30 of detention. Similarly, the course on innovative library services, which addresses not only managerial participatory methods, but also methods of including the public in the media library, places the trainees in an “active set up” that impacts and motivates them. The trainer creates collective thinking and gives the trainees the power to act: they become the driving force in her course. We have very good feedback from the auxis on these days, while the more “classic” days, even if they are necessary in preparation for the exams, are more difficult for the group. Interns who have the most difficulty keeping up will tend to ask for more breaks on these “classic days” than on more interactive days. A trainer presenting a sector of the publishing industry brings books to show them, but to save time, her course being very dense for so few hours, she presents the books and lets the trainees in turn look at the books only during breaks. This creates great frustration among trainees who absorb a large amount of information during the day, without experiencing the pleasure of “touching” and seeing for themselves.

The Acquisition Committee

Aiming to co-construct, LCV hosts a training day together with a bookseller. The objective of the day is, first, to present the profession of bookseller, an important role in the book trade and in obvious relationship with libraries in France, since librarians buy books from partnered bookshops. Secondly, and in the interests of the non-profit’s transparency, the collection’s charter31 detailing the non-profit’s documentary policy (in particular the acquisition policy) is presented to trainees on that day. Finally, the acquisition committee takes place, based on the acquisition policy and the selection criteria presented, but also on the presentation of a pre-selection by the bookseller. The committee can be organized around a theme or from a list of booksellers’ favourites and new releases. The salaried team talks with the bookstore beforehand to give it indications. Having organized it several times, I [Lena] gave very broad indications, asking to provide all types of documents for all audiences, having recent documents as the main criterion. Only a few exclusions were expressed, relying, as always, on the non-profit’s documentary policy: works intended for a university-type audience, for example, or school books (no textbooks are included), etc.

The trainees meet in each library, with a defined budget (200 to 300 euros per library depending on the annual budget) to select works, taking into account the collection charter presented beforehand. In addition to teaching them to follow a budget, accounting for the discount for libraries32, the exercise, above all, allows them to choose the books themselves and therefore to be the first mediators with library users. This increases library assistants‘ involvement and gives them a certain responsibility. As they are the ones who welcome the public all week, training is essential. It gives them the means to understand how to provide the most professional welcome possible. On the other hand, the trainers must adapt and be particularly attentive to the challenges of prison libraries. Indeed, certain practices in prison libraries are very different from those of a municipal library, “for inmates, using the services of libraries in prisons is one of the rare occasions when they are granted autonomy and responsibility to make the choice to read and which subjects they wish to learn (…) by working closely with organizations outside of the prison environment, they [libraries] are a link to culture, events and services outside the prison environment” (Krolak, 2020). It is therefore important to create places for exchange, so auxis can help each other face these challenges. Once a week, they have the opportunity to meet and exchange in a formal setting. They can also talk informally during breaks, especially during meals.

Reading Time After Meals

At the end of the lunch break, we set up a moment where people read to each other. Unlike the reading circles, to which they are all accustomed since it is part of their training, each trainee presents a book of their choice. In addition to practicing for one of the oral exams they will eventually take (the presentation of documents), this exercise enriches their knowledge of the world of publishing, authors, and types of works. The auxis who are already seasoned readers have no difficulty with the exercise, since they bring the book they are reading. The lighter readers choose a book on site, under our recommendations or those of one of the trainers. Regularly presenting poetry myself, I [Lena] often encourage them to read from a collection of poems or fables. The exercise requires selecting a short passage from a book to read aloud. The trainers also participate. They come with books or texts that are not necessarily present in libraries, allowing trainees to discover other works or other rating systems when the document presented comes from another library. This reading moment, for which they may be shy at first, becomes a ritual every week and allows them to make a transition between the lunch break and the class session in the early afternoon.

What to Remember from this Vocational Programme?

The aim of this programme, which is adapted to the prison environment, is to enable inmates appointed to work at the library with the tools to understand the librarian’s profession and thus welcome the public as professionally as possible. The auxis receive daily support from the non-profit’s salaried team and volunteers. When possible, we support initiatives launched by the auxis in order to revitalize the libraries: the inmate librarians may, for example, wish to set up a chess competition or small workshops; we then liaise with the prison administration to make this possible. They can also highlight the collections with presentation tables (thematic or not), or highlight their favourite books, or even, improve the signage according to requests and feedback from the public (we print the texts they have prepared). These initiatives would probably be less frequent without the training and exchanges they have with the professional trainers, but also with each other. The relationships within the cohort also allow them to compare their professional practices with each other and improve. By exchanging regularly, they support each other and share ideas.

Like the sociological workshop described above, the programme includes the auxis by empowering them. They are no longer mere subjects; they are able to “do” and bring this capacity to act to library users. The presence of the auxis-bibliothèques also strengthens the bonds between the public who frequents the libraries and the libraries, also incarcerated. Auxis are able to guide incarcerated readers, to help (often they are also “public writers”), and to provide information on how detention works. This is precious, especially for newcomers and those facing incarceration for the first time. If the members of the non-profit are the link between the auxis and the administration, the auxis establish the link between the non-profit and the penal population.

Conclusion

What we described in this article is made possible by a salaried and professional team of five people, who bring deep knowledge of the functioning of public libraries and the capacity to work within the constraints of prison to ensure that prison libraries are as “normal” as possible. Vocational training plays an important role in this objective, since library assistants manage the reception of the penal population in each of the libraries. By training them, we make sure to pass on the tools and values of the French public service. We allow them to gain confidence and to pass this on to the inmates who use the library. It should be remembered that, despite international and national recommendations, the recruitment of professional librarians in prisons remains marginal in France.

As workers, we try to keep relationships at the forefront of our initiatives: to create common ground within prison and to promote relations with the civil society from which they are excluded for the duration of their sentence. We value the knowledge of detainees through participatory methodologies. We create spaces that empower, which ranges from the simple act of choosing one’s own book to a session of debates. We also support initiatives from library assistants. As Lisa Krolak suggests, we try to make the prison library strive for an ideal: a transformative potential (Krolak, 2020). In France, the legal framework concerning access to reading and the right to information was initiated in the 1980s, when the abolition of the death penalty had just been enacted. Almost half a century later, this political project was gradually enforced thanks to civil society and the commitment of volunteers. While we wrote this article to make these initiatives known to the general public, we also saw it as an opportunity to reflect on our positions. We hope that they can inspire, in France, and around the world, innovative political acts in favor of prisoners, who are destined to leave prison and reintegrate society.

References

- Chantraine, G. (2005). Expériences carcérales et savoirs minoritaires : Pour un regard « d’en bas » sur la sanction pénale. Informations sociales, 127(7), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.3917/inso.127.0042

- Dehaene, S. (2007). Neurones de la lecture. Odile Jacob.

- Krolak, L. (2020). Lire derrière les barreaux : Le pouvoir de transformation des bibliothèques en milieu carcéral. Institut de l’UNESCO pour l’apprentissage tout au long de la vie. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373456

- Lachaux, J.-P. (2020). L’attention, ça s’apprend ! Ed. Mdi.

- Laplantine, F. (1999). Je, nous et les autres. Le Pommier.

- Nicolas-Le Strat, P. (2024). Faire recherche en commun : Chroniques d’une pratique éprouvée. Éditions du Commun.

- Pelsy-Johann, P. (2017). Entre les barreaux, les mots [Enregistrement vidéo]. Baiacedez Films.

- Rebout, L. (dir.). (2025). Comment construire une subjectivité carcérale : Un chercheur en prison. Phanères.

- Reyzabal, M. V. (1994). La lecture à voix haute (C. Adam, trad.). Revue internationale d’éducation de Sèvres, 02, 83-86. https://doi.org/10.4000/ries.4271

- Stathopoulos, A. (2025). Chercheurs en cabane : Après-propos depuis les coulisses. Dans L. Rebout (dir), Comment construire une subjectivité carcérale. Un chercheur en prison. Phanères.

Notes

- https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/LEGITEXT000006069570/ ↩︎

- Especially when the participants are exclusively male prisoners. ↩︎

- Since May 1 2022, Article R-414-1 of the Prison Code has recommended direct and regular access for prisoners to the books provided by media libraries. Article D-414-2 recalls the role of librarians in the supply as well as the training and supervision of prisoners assigned to the media library. ↩︎

- In France, a remand prison accommodates defendants (awaiting trial) and people sentenced to less than 24 months. A detention centre accommodates persons sentenced to more than 24 months. There are also prisons that accommodate people sentenced to very long sentences (generally more than ten years). In practice, remand prisons are often overcrowded because they do not apply a quota, unlike the other two types of establishments. Some detainees in remand prisons sometimes wait for more than two years to be placed in a detention centre or central prison. ↩︎

- https://www.leparisien.fr/essonne-91/prison-de-fleury-merogis-le-nouveau-centre-de-detention-ferme-les-detenus-sont-transferes-26-09-2024-FW2RAEULGBFFDB32TSBPHTFSWU.php ↩︎

- For figures, please refer to the table “Description of the various detention buildings of the Fleury-Mérogis Prison and the composition of the libraries” in the appendix. ↩︎

- In French prisons, with the exception of the playground and the library, there is no space where detainees can meet without the presence of a guard. They are locked in their cells 22 hours a day. Even meals are distributed directly in the cells. ↩︎

- The first names of detainees are changed or anonymised. ↩︎

- Show of 01/12/2023 broadcast on France 2, excerpt from the column “L’œil de Pierre Lescure.” ↩︎

- See the website of the Ministry of Justice: https://www.justice.gouv.fr/actualites/actualite/prix-goncourt-detenus-2022-15-romans-selectionnes ↩︎

- For the 2024 edition, the number of participants was estimated at nearly 600. On January 1, 2025, 79,300 people are incarcerated in France, according to the ministry’s website: https://www.justice.gouv.fr/documentation/etudes-et-statistiques/79-300-personnes-detenues-au-1er-janvier-2025 ↩︎

- Editors’ note: France has four penal jurisdictions and this sentence if referring to the correctional and criminal jurisdiction. The former is designed for offences that are subject to sentences between 5 and 10 years and the later is designed for crimes that are subject to sentences of 15 to 20 years of reclusion. ↩︎

- The book addresses the harsh living conditions of homosexual people in Morocco. ↩︎

- These testimonies are taken from my [Bernadette] notes, taken on the spot during the sessions of the Prix Goncourt. I trace the evolution of the opinions of each one as the sessions progress, allowing me to then see the evolution of the opinions on the many books in the running. ↩︎

- Testimony taken from the programme C à vous of 01/12/2023. ↩︎

- Testimony taken from the programme C à vous of 01/12/2023 (as before). Many similar, informal testimonies are sent to us by the participants throughout the sessions of the Goncourt Prize for Prisoners. ↩︎

- Mixed activities require a significant mobilization of the prison administration (mainly for security reasons), which reduces their quantity and frequency. It is therefore a rather exceptional measure and concerns a very small number of detainees. As a cultural non-profit, it seems essential to us to maintain mixed activities as much as possible, since it is in these conditions that prisoners will return to an “open” society. Indeed, whether in the family, friends or professional sphere, there will be diversity. ↩︎

- “A researcher in prison. How to build a prison subjectivity”: https://calenda.org/1119618?file=1 ↩︎

- Question from Denis Samnick (Doctor of Sociology, Institute of Development Policy, University of Antwerp): “[…] Researchers who were generally incarcerated first take a step back, they analyze from a distance. […] But they are already inside and they are already rationalizing from the inside. Can they perhaps envisage […] to see how from within we are already beginning to rationalize, and how this rationalization […] can evolve over time?” ↩︎

- Excerpts from the transcript of the meeting of April 24, 2025. ↩︎

- Excerpts from the transcript of the meeting of April 24, 2025. ↩︎

- Translation from the editors. ↩︎

- We refer here to the recent controversy launched by the Minister of Justice Gérald Darmanin about the “playful and provocative” activities that he forbade by memo in February 2025. For more information on this subject, the website of the International Prison Observatory (IOP), French section, is particularly extensive. https://oip.org/analyse/activites-ludiques-lengrenage/ On 19 May 2025, following legal action brought by seven French organizations (including the OIP), the Council of State annulled the ban on “recreational activities,” deeming it contrary to the prison code. See: https://oip.org/communique/suppression-dactivites-en-prison-une-action-en-justice-pour-sauvegarder-le-droit-a-la-reinsertion/ ; https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2025/05/19/le-conseil-d-etat-annule-l-interdiction-des-activites-ludiques-en-prison-annoncee-par-gerald-darmanin_6607190_3224.html ; https://www.lefigaro.fr/actualite-france/interdiction-des-activites-ludiques-en-prison-le-conseil-d-etat-annule-la-circulaire-de-gerald-darmanin-20250519 ↩︎

- However, some activities target a defined penal population. For example, we set up writing workshops specifically for allophones or people unable to read or write. These people can participate in all our activities, but, in order to work and fight against all forms of exclusion, we are committed to developing actions dedicated specifically for them. We are only sorry that we cannot do it on a larger scale due to a lack of resources (human and financial). ↩︎

- More information on this subject is available on the French website dedicated to the book and reading projects for people in custody: https://lecture-justice.org/ressources/guides-et-fiches-pratiques ↩︎

- As explained above, mixed activities are rare in prisons in France. Lire C’est Vivre mainly organises two mixed activities: the Goncourt Prize for Prisoners (which concerns about six women and fourteen men) and vocational training (about two women and ten men) with the support of the prison administration. For this part, we therefore opted for inclusive and masculine form for by number agreement. ↩︎

- For the years 2024–2025, the hourly rate is €2.5. ↩︎

- This part is written in the feminine, as the training team being composed of about ten women and one man. This balance is fairly representative of the share of professional library professionals in France, who are under-represented in the profession. ↩︎

- There can be major differences between working in a university library, where the public is almost entirely made up of students, professors and researchers, and working in a library in the city of Paris, a highly urbanized environment. But even between the 18th arrondissement, a working-class neighborhood and the 7th arrondissement, a wealthy neighborhood, the public differs greatly. In addition, the libraries of Paris operate in a network (possibility of borrowing from all the libraries in the city with the same borrowing card). There are also differences with working in a small village in the south of the Paris region, with a much lower population density. In these rural media libraries, there are often volunteers who accompany the librarian, who is the only employee, or sometimes there is no employee at all, and volunteers are responsible for the whole library. The opening hours are then very short. ↩︎

- Prisoners have no control over their daily prison life. They are constantly subjected to changes in schedules, waiting for the door to be opened to them, to do an activity that they have asked for or for an extraction that is imposed on them. All this hinders their ability to concentrate since they can never count on a certain amount of time. In addition, the prisons in France are all overcrowded and the 9 m2 cells are shared by a minimum of two people, a third person often crammed on a mattress placed on the floor. In these conditions, the television often remains on 24 hours a day, further deteriorating the ability to concentrate. ↩︎

- Libraries in France generally draw up a collection charter allowing them to define the institution’s documentary policy: this concerns the acquisition criteria as well as those of weeding (removal of works), but also cultural programming. ↩︎

- In France, books benefit from a law imposing a single price: the same new book costs the same price, regardless of where it is sold (an independent bookstore or not, an online platform, etc.). Second-hand books are not covered by this law. This same law allows businesses to apply a maximum discount of 9% to libraries open to the public. See Law No. 81–766 of 10 August 1981 on the price of books, Article 3, 2nd paragraph: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000000517179/ ↩︎

Appendices

Appendix 1: Acronyms

- LCV: Lire C’est Vivre Non-profit

- CPFM: Fleury-Mérogis prison (including the remand prison and the detention centre)

- MAFM: Fleury-Mérogis prison

- MAH: Men’s Prison

- MAF: Women’s Prison

- D1, D2, D3, D4, D5: Men’s Detention Building (followed by building number)

- QD: Disciplinary Unit

- D3IS: Segregation unit located on the 4th floor of Building D3

- D3IT: Total isolation unit located on the 4th floor of Building D3

- QM: Miners’ Quarters

- QER: Radicalization Assessment Unit

- NURS: Nursery area where pregnant women from the 6th month and mothers with their child (babies under 18 months) are incarcerated

- IQ/D: Solitary confinement/disciplinary unit (the women’s remand prison is smaller than the men’s prison, so the two sections have been combined).

Appendix 2: Descriptive table of the various detention buildings of the Fleury-Mérogis Prison and the composition of the libraries

Authors

Lena Sarrut

Staff librarian with the Lire C’est Vivre association (2018 to 2025)

Doctoral student on issues of expression in prison, CEAC laboratory, University of Lille

Member of the training commission of the Association des Bibliothécaires de France

sarrut.lena@gmail.com

Nicole El Massioui

Volunteer and board member of the Lire C’est Vivre association

Co-leads two reading circles, one in a men’s building and the other in a women’s building

Retired neuroscience researcher

nelmassioui@gmail.com

Bernadette Buisson

Volunteer with Lire C’est Vivre association

Co-hosts a reading circle and sessions of the Prix Goncourt des détenus

Retired pediatrician

bbuisson1@orange.fr

Alexia Stathopoulos

Volunteer with Lire C’est Vivre association

Leads a co-constructed introductory sociology workshop

Independent researcher, scientific collaborator at CRID&P, UCLouvain

alexia.stathopoulos@gmail.com

Cite this article

Sarrut, L., El Massioui, N., Buisson, B. et Stathopoulos, A. (2025). Prison Libraries: Building Collective Knowledge. The Case of the Libraries of the Non-profit Lire C’est Vivre at the Fleury-Mérogis Penitentiary Centre, France. Apprendre + Agir, special issue 2025, Learning and Transforming: International Practices and Perspectives on Prison Education. https://icea-apprendreagir.ca/prison-libraries-building-collective-knowledge-the-case-of-the-libraries-of-the-non-profit-lire-cest-vivre-at-the-fleury-merogis-penitentiary-centre-france/