Special Issue 2025 of Apprendre + Agir

Richard Mayrand

Abstract

In this article, the author recounts his experience at the Portage Centre at Lac Écho, a specialized addiction rehabilitation facility. For the past 25 years, he has been meeting with teenagers to discuss the challenges of their struggle with addictions. This activity is based on the use of two cultural references, Plato’s allegory of the cave (classic reference) and The Truman Show (popular reference) to promote critical thinking, self-awareness and the development of life skills. The author describes the activity, the topics of discussion, the participants’ reactions, the improvements made over time, the guide to facilitate further reflection after the activity, and the recommended practices for this type of activity. Finally, the author proposes ways to deploy this activity beyond the framework of Portage.

Long summary

This article explores an innovative pedagogical approach implemented in a rehabilitation centre for adolescents and young adults in vulnerable situations struggling with addictions. The activity is based on the joint use of the film The Truman Show and Plato’s allegory of the cave as tools for reflection and self-awareness. After being introduced to both works, which share a powerful metaphorical potential, the young attendees are invited to reflect on the mechanisms of illusion, control, social conditioning and liberation, in direct connection with their own life trajectory and therapeutic journey.

The activity is part of a psychosocial support program conducted at the Portage Centre, an institution known for its humanistic and community-based approach to youths at risk. For more than 25 years, discussion groups have been organized around the viewing of the film The Truman Show, followed by a parallel with the Platonic allegory. The latter is presented in an accessible and contextualized way, often in the form of a dialogue or an explanatory diagram, in order to make its message understandable for an audience not trained in philosophy.

The heart of the activity is based on the analogy between the illusions of the protagonist Truman Burbank—brought up without his knowledge in a fabricated reality show—and the conditioning or beliefs in which young people have been trapped, sometimes since childhood, by their environment, their addictions or psychological survival mechanisms. The process of “coming out of the cave,” as described by Plato, thus finds a powerful echo in the journey of detoxification and self-redefinition initiated by the teenagers at Portage. The light, in the allegory, as in the film, symbolizes here not only the truth, but also the pain of unveiling, the discomfort of change and the vertigo of regained freedom.

This approach suggests a form of philosophical education applied to the concrete reality of young people in rehabilitation. It allows them to think critically about their past and present, while imagining a future free of old constraints. Far from being a simple intellectual exercise, this reflection becomes a lever for personal transformation. Over the years, several young people have testified to the decisive role played by this activity in their awareness of their conditioning, their fears, their toxic attachments and their ability to redefine themselves.

The article also addresses the limits of the exercise, in particular the difficulty of maintaining the attention or understanding of some participants, or the resistance to a symbolism perceived as abstract. However, these challenges are often overcome by the quality of the presentation, the use of concrete examples from the lives of young people and the encouragement of authentic dialogue.

In conclusion, this practice illustrates the interest of using strong cultural and philosophical tools to accompany the rehabilitation processes. It also testifies to the potential of philosophy as a vector of emancipation, including (and perhaps especially) among audiences often excluded from traditional forms of intellectual reflection. Plato’s allegory of the cave, far from being just an object of academic study, becomes here a mirror and a compass for those who seek to free themselves from their inner chains.

Keywords: plato’s Allegory of the cave, The Truman Show (film), young people in vulnerable situations, dependence and personal liberation, critical Thinking and Self-Awareness, philosophical Education in Social Intervention

Portage, Truman, Plato and the origin of the project

The development of the next generation has always been important to me. Whether it’s teaching alpine skiing, hosting pharmacy interns or teaching at the Faculty of Pharmacy at the Université de Montréal, the desire to give back has often guided my journey. However, nothing predestined me to try to make a difference, however small, with teenagers struggling with addiction.

This project came about by a happy coincidence. First, during a visit to the Portage Centre at Lac Écho, I met caring and passionate people who work there, as well as young girls and boys who are facing immense challenges related to their addiction and seeking to rebuild their lives on a stronger foundation.

Portage is a non-profit organization whose mission is to help people with substance abuse problems overcome their addiction in order to lead sober, fulfilling and productive lives. Since its founding in 1970, Portage has supported thousands of people through specialized rehabilitation programs for adolescents, adults, pregnant women, mothers with young children, people living with mental health disorders, Indigenous communities and people in the criminal justice system. The organization also offers complementary services: employment training, aftercare, social reintegration support and community housing.

The young people housed at the Portage Centre commit to a therapeutic program lasting about six months. With each visit, I am touched by what I observe: exchanges of respect, humanity and authenticity between the workers and the youngsters. The efforts to break the chains of addiction are clear and inspiring.

A few weeks after my first visit to Portage, I watched the movie The Truman Show, directed by Peter Weir and starring Jim Carrey. The film tells the story of Truman, a young man filmed without his knowledge 24 hours a day in a huge television studio, where he has lived since birth. He thinks he lives in a normal house in a real city, but everything is fictional. His parents, his wife, his best friend, his colleagues and the other residents are actors. Truman lived in a total illusion, a “false reality,” without being aware of it. Little by little, certain elements of his life seem incoherent to him. He then begins to doubt, then to seek, hesitantly but determinedly, a way out. His quest becomes deeply moving.

The film’s script leads the viewer to see what Truman cannot perceive, given the manipulation of which he is a victim. The film thus encourages the audience to identify authentic and false elements by using critical thinking. Under the guise of comedy, the script of The Truman Show offers an astonishing parallel with Plato’s allegory of the cave.

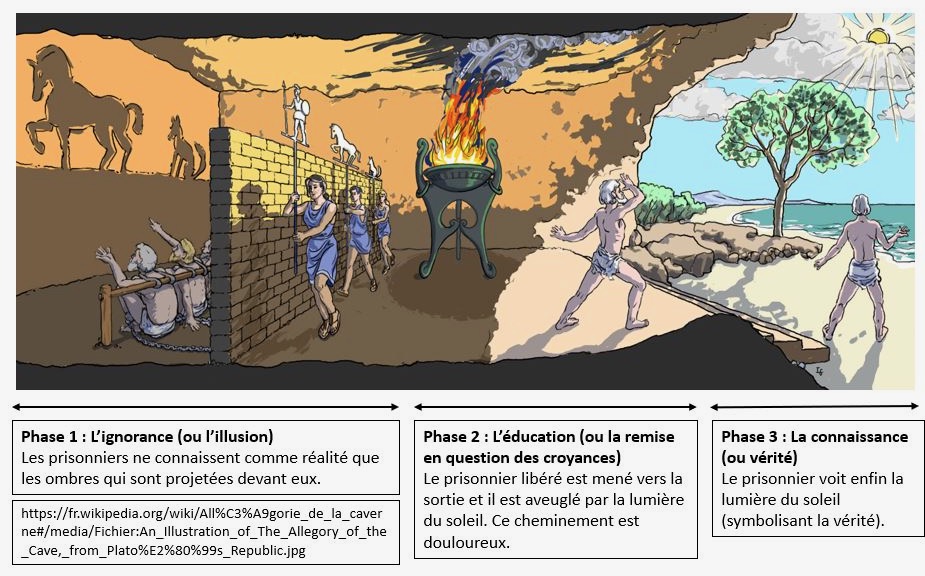

In the allegory of the cave, Plato describes prisoners chained in a cave, seeing only the shadows of objects projected on a wall. These shadows represent their only reality. One of the prisoners is freed and discovers, after a painful ascent, the outside world and the sunlight, a symbol of truth. When he returns to others to share his discovery, he is rejected. It is interesting to note that for Plato, this freed prisoner, who eventually seeks to share what he has learned, plays a role similar to that of the philosopher who tries to guide his students despite misunderstanding.

Plato thus bequeathed us a powerful metaphor for exploring complex concepts, such as ignorance, questioning beliefs, and knowledge (or truth).

Source: Wikipedia, notes added by the author

The allegory demonstrates how difficult it is to free ourselves from these illusions, which we believe to be real, to reach a higher level of consciousness than the one in which we live. The strength of this story lies in its simplicity, which makes it accessible to audiences with various capacities for abstraction. Everyone can identify with these prisoners, who are unable to see what seems obvious to those who live outside the cave. This story invites us to deeply question the way we interpret the world and our interactions with it. For my part, since studying the allegory in a philosophy class in Cégep, I have been using it as a tool for reflection: what elements of my life are part of a reality on which I can base my decisions? Which are more illusions?

This connection between The Truman Show and the allegory of the cave came to me shortly after my visit to Portage. A question then came to me: could we establish a link between (a) Plato’s prisoner, who does not try to flee his condition (unless forced to do so) because he is unaware of the existence of another world; (b) Truman, who discovers he needs to escape even without knowing what awaits him; and (c) those young people I met, some of whom are trying to “get out of their addiction,” and others who have not yet become aware that their drug addiction is their own cave?

This question naturally guided my thinking. I suggested to the Portage management that we lead an activity based on the viewing of The Truman Show, followed by a group discussion around the themes of the film and the allegory of the cave. In April 2000, about twenty teenagers living at the Portage Centre at Lac Écho welcomed me for this first meeting. The activity was received well enough that the experiment was repeated.

In January 2025, I hosted “Truman at Portage” for the 25th consecutive year. I host this activity twice a year, during the holiday season and at the beginning of summer. These visits every six months coincide with the usual length of stay and thus make it possible to reach two cohorts of young people. On each visit, we watch The Truman Show together and discuss their experiences in light of Truman’s story and Plato’s allegory.

Typical Schedule for a “Truman in Portage” Event

The “Truman in Portage” event lasts a little over four hours and includes a meal at the beginning of the activity. Depending on the particular contexts at the time of the visits, we sometimes hold the event during the day or in the evening.

The activity includes the following steps:

- Preparation of the activity

I proofread the facilitation material in the previous days and prepare thematic posters to encourage the mobilization of participants during the discussion. I ask for the list of the teenagers’ first names, which I memorize in order to foster a relationship of trust during the first exchanges.

- Coordination Meeting of the Activity With the Portage Team

When I arrive, I meet with the Portage team to take the pulse of the group and adapt the schedule if necessary. I identify newcomer participants, who may be more vulnerable or less engaged.

- Introductory Remarks and Presentation of the Activities’ Agenda

I introduce myself and explain the reasons for my presence at Portage. I will briefly describe the course of the activity, mentioning that we will watch the movie The Truman Show and discuss it together afterwards. I also introduce the allegory of the cave, without revealing the links between the two works. Finally, I invite everyone to participate fully in the discussion in order to reap the maximum benefits.

- Special Group Meal

A pizza dinner is offered, helping to create a relaxed atmosphere conducive to exchanges. It’s an appreciated gift. I take the opportunity to circulate among the tables and engage in conversation.

- Break

This pause, before the viewing, allows everyone to prepare themselves in order to be able to maintain their attention throughout the film.

- Screening of the film The Truman Show

The film is screened in two rooms, in French and English. The rules of life established by Portage contribute to the establishment of an atmosphere conducive to attentive listening.

- Break

This break allows teenagers to prepare for the discussion that follows, which also requires an effort of attention and reflection.

- Directed discussion about the film

A discussion structured around ten themes follows the screening. This is the part of the activity that opens the way to several learnings. Volunteers take turns writing down their colleagues’ comments on posters. This way of doing things keeps everyone interested.

- Closing Remarks and Thanks

The closing remarks are an opportunity to highlight the efforts of the group, to express our mutual appreciation and to conclude on a note of encouragement and hope. This moment is often rich in emotions.

- Debriefing with the Portage team

This short discussion allows us to gather feedback from the staff members and to thank them for their welcome and support during the event.

A Facilitated Discussion

The facilitated discussion is structured around ten carefully chosen themes. Whenever possible, a theme is addressed through a question related to Truman’s experience, allowing teenagers to first share their observations related to the film. This detour through fiction, less intrusive, facilitates the beginning of reflection. Once this field has been explored, the discussion then pivots to the participants’ experiences in order to identify “parallel situations,” if any. This two-step approach is conducive to introspection, and opens the door to often personal and authentic sharing.

Theme 1 — The general meaning of the film (opening remarks to break the ice)

- What did you think of the film?

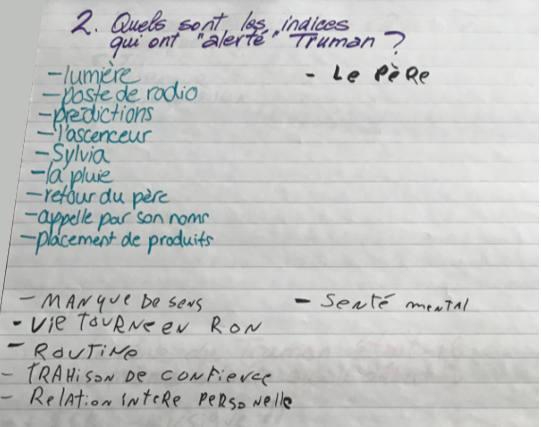

Theme 2 — The clues that lead us to question ourselves.

- What clues led Truman to think that his reality was not as authentic as he believed?

- In your personal life, what are the clues that lead you (or have led you) to question beliefs that you have (or that you had)? (Illustration 3—Poster for them 2)

Theme 3 — The dreams that motivate us

- Did Truman have any dreams that he wanted to achieve? What were they?

- What are the dreams you would like to fulfill?

Theme 4 — Dreams that evolve

- By the end of the film, has Truman fulfilled his dream as he envisioned it? Will he need to go to Fiji? Why?

- How might this influence the way you think about your dreams?

Theme 5 — The obstacles ahead of us

- What challenges did Truman have to overcome?

- What are the things that hold you back in your efforts to change your perception of yourself and the reality around you? Which of those elements do you have the most control over? Which ones do you have the least control over? Why?

Theme 6 — People and resources that can help us and those that don’t

- Who could Truman rely on to free himself from the challenges he faced? Who could he not trust?

- Whom can you count on in your journey to change your perception of yourself and your reality, and then live according to your new vision of reality? Who should you not trust?

Theme 7 — The qualities required to move forward in this journey made up of a series of challenges.

- What qualities did Truman demonstrate through these challenges?

- What qualities will you need to enable you to take on the series of challenges that lie ahead? How could you acquire these qualities if you do not yet possess them?

Theme 8 — Reward at the end of the effort

- What are Truman’s feelings when he manages to free himself?

- How will you feel when you succeed too?

Theme 9 — To each his or her own journey

- At the end of The Truman Show, what has changed for viewers? Have they begun their process of liberation?

Theme 10 — Each of us in search of our truth

- What is the connection between the cave described by Plato and the giant studio in which Truman lived without knowing it?

- How do you feel concerned by the lessons of the allegory of the cave and the Truman Show?

Accompanying Guide to Continue the Reflection After the Event

For the past few years, a guide to the Truman activity at Portage has been given at the end of the event. Participants can answer, at their own pace and in complete privacy, in the days that follow, the questions that have already been addressed in the group.

We are currently exploring the possibility that the material covered may also be discussed in class in the program under the responsibility of a school service centre or a school board.

Participants’ Reactions

The evaluation of the activity is based on two sources: periodic surveys and feedback gathered through informal discussions.

The surveys are composed of a “multiple-choice questions” section, which can be illustrated quantitatively, followed by a qualitative section in the form of comments. The quantitative assessment is conducted by assigning a score based on the following scale: Not at all: 0; A little: 1; Moderately: 2; A lot: 3. Fifteen participants responded to the 2019 edition of the evaluation.

These results indicate that the activity is generally well liked by the participants, particularly for the first three elements of the survey which concern more playful elements (watching a movie, eating pizza). For the last three elements, we observe that the grades awarded have fallen slightly. This slight decline seems to be related to the fact that these aspects (participating in a discussion, evaluating the usefulness of the activity in the short or medium/long term) require additional effort, particularly on the cognitive and emotional levels. Over the years, I have noticed that adolescents at the beginning of therapy generally seem to show more difficulties in terms of reflective capacity and commitment than those who are nearing the end of the program. This difference may explain, at least in part, why the scores for the last three items are lower.

Despite this, the “utility” component of the questionnaire offers several lessons. On the one hand, both results remain high given the challenges that participants will face. On the other hand, if these results are lower than those related to the actual unfolding of the activity, they indicate that the participants understand that the success of the workshop does not guarantee, on its own, the success of their approach to Portage. Finally, the score for “usefulness after Portage” is lower than “during Portage” and suggests that participants are aware of the increasing uncertainty as time goes further away.

To the question: “How could watching the movie The Truman Show and the discussion we had help you in your process? ”, the following answers emerge (translated from French by the editors, tone and language register kept as faithful to the original as possible):

To introspect on myself in order to free myself from my cave.

To question myself about myself.

I think I just have to ask questions.

Open my eyes.

To know more about the opinion of others. Also to give motivation.

The fact that Truman never gave up and he eventually succeeded proves to me that in life anything is possible.

To better understand where I have gone.

Of how I see life and how I do it.

To help me break through and believe in myself and my goals.

It leaves me thinking that it’s better to aim high because I’ll already go higher than at the beginning since I’m the only person I really have to trust.

Not accepting people’s first answers and also not closing my eyes to the things that are happening around me.

To step on my fears because in the end he will have something more beautiful.

To be able to use the reflection for future problems.

To be able to believe in my choices more.

To take a look at what’s going on in my life.

Here are also some general impressions of the participants, also reproduced in full.

Keep it up!

Thank you very much, it did me a lot of good. : )

I really enjoyed the activity and your approach, you are good people, it shows.

Thank you, I have understood things.

The participants are grateful that an outsider, who does not know them, dedicates a day to them, learns their first name, listens to their voices and reacts to them. Beyond the reflection on Truman and the allegory of the cave, this meeting shows them that they have value.

Finally, the feedback reveals that the activity succeeds, for many, in opening a new window on the world and the place they occupy in it. The Allegory of the Cave and The Truman Show equip them to analyze, with hindsight, the situations they are already experiencing and will continue to experience. For example, during my most recent visit (June 2025), a teenager showed that he was taking ownership of the concept by asking me: “Richard, what is your cave?”

Portage workers confirm that the workshop fits well into the therapeutic process. A telling anecdote is that one of them told me, “Richard, when I was a resident at Portage, the Truman activity was a turning point in my recovery process.” Former participants coming back to Portage as counsellors, is a nod to Plato: some “prisoners” return to help those left behind.

Continuous Improvement of the Truman Activity in Portage

Over the years, the activity has been enriched by several concrete adjustments: the organization of a special meal at the beginning of the day; the formalization of a plan for a guided discussion; the use of giant posters to record participants’ comments; the distribution of a booklet promoting personal reflection; the periodic use of a survey to gather feedback; as well as collaboration with the UNESCO Chair in Applied Research for Education in Prison at Cégep Marie-Victorin, with the aim of evaluating the activity and, potentially, its longer-term impact.

The writing of this text, combined with the comments of the editorial committee, has fuelled a reflection on new avenues for improvement, particularly with regard to the space given to the allegory of the cave, during the exchanges. So far, the initial explanation and the connection between Truman’s studio, Plato’s cave, and drug addiction are generally well understood by participants at the end of the activity. However, it seems possible to go further.

To this end, three improvements are planned for future editions:

- Visually integrate the allegory from the beginning of the activity, using the illustration reproduced above, in order to complement the explanations on the three stages of the liberation process (chaining, discovery, exit).

- To further structure the facilitated discussion by asking participants, at different points in the viewing, to situate Truman in his journey in relation to these steps.

- Conclude the group discussion by inviting each adolescent to identify, if he or she wishes, the stage of the release process in which he or she recognizes himself or herself at that moment in his or her journey.

This approach should allow a greater number of participants to actively situate themselves in relation to the concept of allegory, while promoting a personal appropriation of the message.

Naturally, these adjustments will have to be integrated into the accompanying guide, in order to ensure their consistency with the overall activity.

Interventions with Participants to Maintain a Favourable Learning Dynamic

On very rare occasions, I have had to temporarily suspend the activity to manage a situation where a teenager was disrupting the process. Over the years, I have learned to intervene based on the codes already known and shared within the community.

For example, a simple but effective rule allows anyone present, speaker, participant or guest, to ask to speak by simply raising their hand. When one hand is raised, the others raise theirs in turn and stop speaking. This collective control mechanism ensures that, gradually, the sound level decreases until complete silence sets in.

Once calm has returned, the person who raised his hand can express himself. I then take the opportunity to name what I observe and what I feel, in a respectful and non-judgmental way. Generally, a participant who is more advanced in his or her journey then intervenes to support my message and relay the call to preserve a proper atmosphere for the activity.

This mode of intervention is in line with the spirit of the “therapeutic community” specific to Portage, where teenagers who have been living for several months play an active role in the cohesion of the group. Thus, the participants are not mere receivers of instructions: they become, in turn, agents of regulation and models for others.

Collaboration with the UNESCO Chair in Applied Research for Education in Prisons at Cégep Marie-Victorin

Five years ago, I contacted representatives of the UNESCO Chair in Applied Research for Education in Prison at Cégep Marie-Victorin, as I was looking to gather feedback from leading figures in the field of education in prisons and pre-incarceration environments. We agreed that the Truman activity at Portage was fully in line with the Chair’s field of interest, given that the young people targeted by the activity are often at the frontier of the legal system. In addition, this activity is a form of informal training aimed at providing participants with new life skills.

Marc-André Lacelle, the Chair’s Development and Research Advisor and Principal Investigator, has agreed to lead a project to develop an impact analysis framework. This framework could eventually be used to measure the impact of the Truman activity at Portage, as well as other comparable projects. Camille Trembley, coordinator and pedagogical advisor at the Chair, also joined the project.

This collaboration also led to participation in the “poster communication” component of the Montreal International Meetings on Prison Education held at UQAM in October 2024.

Best Practices: Tips for Hosting a “Truman” Event (or any adaptation)

In hindsight, several factors proved to be decisive in Truman’s success at Portage. The recommendations below are the result of years of learning in the field; They could be useful in guiding any person or team wishing to create a similar activity.

Before the activity: laying a solid foundation

- Prepare for each session: even if it is not a first edition, review the equipment, schedules and roles.

- Choose a symbolic moment: focus on a time when the feeling of distance is more acute (for example, the holiday season or the end of the school year).

- Plan a welcome meal: a concrete gesture of generosity that immediately creates a warm atmosphere and facilitates exchanges.

During the activity: creating a climate of trust

- Offer a significant presence: the visit of the facilitator, a recognized and esteemed external person, is perceived as a thoughtful gesture that values the young people and reinforces their sense of importance.

- Systematically use first names: each teenager feels recognized and prioritized.

- Valuing the local team: publicly acknowledging the daily work of the counsellors increases their credibility with the group.

- Know your limits: without training in psychotherapy, stay in the presentation of concepts and leave the therapeutic component to the Portage professionals, who are always present.

- Follow a structured discussion plan: catalyze participation while avoiding deviating from educational objectives.

After the activity: prolonging the impact

- Provide a support guide: allow everyone to continue the reflection at their own pace, alone or with a counsellor.

- Conduct a feedback survey: measure appreciation and identify areas for continuous improvement.

- Collaborate with research partners: document the process and impact (e.g., the UNESCO Chair in Applied Research for Education in Prison).

The heart of the Truman experience at Portage is rooted in the combination of two complementary cultural references, Plato’s cave allegory and the film The Truman Show. The film offers an accessible and emotional story that makes it easier to identify with the issues of control and authenticity. The allegory brings philosophical depth and critical perspective, transforming entertainment into existential reflection.

Isolating one or the other would reduce the mobilizing effect, as their combination produces a richer and more lasting dynamic. The improvements envisaged for future editions are precisely aimed at making even better use of this complementarity.

Truman-Plato-Portage: A Paradox in the Background

Portage’s distinctive approach to supporting people struggling with addiction is based on a process of self-discovery that takes place in a closed treatment setting. This framework may seem paradoxical: how can a move towards freedom, as evoked by Plato in the allegory of the cave, begin with voluntary confinement?

In my eyes, this closed treatment program constitutes a form of retreat, both temporary and chosen, which acts as a path, a corridor towards the light, to use the Platonic image. It provides a protected space where reflection, unlearning, and transformation can emerge away from the toxic influences of the outside world.

This paradox finds a direct echo in Plato’s texts, where the prisoner is not freed of his own accord, but forced to leave the cave. This imposed, painful but necessary movement strongly resembles the journey of Portage residents, who are often involved in the program following a difficult decision, sometimes even in a tense legal or family context.

I intend to address this paradox more explicitly in future editions of Truman at Portage. Indeed, the stay at Portage is a demanding challenge, often accompanied by moments of suffering, discomfort and anguish. The fact that Plato anticipated these pains in the journey towards truth allows adolescents to recognize themselves in this process: they are not alone, and what they are experiencing is part of an ancient, universal and meaningful human dynamic.

In fact, isn’t Portage’s entire journey summed up in its own logo? It shows a bird first locked up in a restricted space, which then begins a movement of elevation, before launching itself fully towards freedom. This image, heavy with meaning, echoes Plato as much as Truman. It aptly illustrates this apparent paradox: it is sometimes within a framework, real or symbolic, that the desire, and then the ability, to stand on one’s own two feet can emerge.

Conclusion

After each Truman meeting at Portage, I leave with a new energy, a form of silent recognition for these moments of exchange, lucidity and courage.

On the occasion of the 25th edition of this activity, I ask myself: where could Truman and Plato go now? Why not imagine a version of the activity in Leclerc, Donnacona or Port-Cartier? And why not get out of the prison setting to offer variations elsewhere, such as Le Chaînon, the Auberge Madeleine or in organizations that help men in difficulty? The activity could also find its place in adult education programmes, where people seek to rebuild their relationship with themselves, their history and their future.

The potential of this activity is immense. It lies in the improbable encounter between a contemporary cinematographic work, a thousand-year-old philosophical allegory and the singular life stories of the participants. This juxtaposition triggers awareness, gives rise to meaningful dialogues and calls for transformation.

If some people wish to try the adventure, I will be happy to share my experience, to accompany you in the planning of your project and, who knows, to travel to be present during your first presentation of the Truman event, in the environment that is close to your heart.

Author

Richard Mayrand, pharmacist

Guest Facilitator, Portage (Addiction Therapy Centre)

Chairman of the Board of Directors, Montreal Clinical Research Institute (IRCM)

Former Vice-President, Pharmacy and Government Affairs, Jean Coutu Group, Subsidiary of Metro

rmayrand@richardmayrand.com

Cite this article

Mayrand, R. (2025). Developing an Informal Training Activity for Teens in Pre-judicialization Situations: The Example of Truman in Portage. Apprendre + Agir, special issue 2025, Learning and Transforming: International Practices and Perspectives on Prison Education. https://icea-apprendreagir.ca/developing-an-informal-training-activity-for-teens-in-pre-judicialization-situations-the-example-of-truman-in-portage/