Special Issue 2025 of Apprendre + Agir

Lucie Alidières

Abstract

This article analyzes the ways of learning in prison based on a qualitative study carried out in several prisons as part of the European project SPOC in Prison. The scientific approach chosen combines the observation of learning situations involving the use of disconnected digital tools, especially designed for the prison environment, and the analysis of language practices (speaking, formulating, adjusting, negotiating). This dual linguistic and technological focus highlights how learning is built on a daily basis, through words, gestures, postures and situated uses of digital technology. The study shows that adapted pedagogical engineering can support the articulation between formal education (school teaching), non-formal education (workshops, training) and informal education (mutual aid, experiential knowledge). It is based on the scripting of content, the functional sobriety of interfaces and the consideration of specific usage regimen (absence of Internet, limited access, human support). Human mediation appears to be an essential vector: it facilitates the appropriation of the modules, stimulates participation and increases the value of implicit knowledge. The learning of digital literacies—considered as situated and critical social practices—thus becomes a lever for transformation, provided that it is thought of from the field. The article invites us to consider educational practices in detention as situated forms in their own right, capable of opening up spaces that carry meaning, recognition and emancipation.

Long summary

Prison is a highly constrained environment, marked by confinement, the strict regulation of activities and the fragmentation of temporalities. In this context, education is an important lever for reintegration, but remains affected by many material, institutional and symbolic limitations. This article proposes to examine educational practices in the French context through an interactional approach focused on digital technologies and based on an experiment conducted as part of the European project SPOC in Prison (Small Private Online Courses in Prison).

After tracing the evolution of education in French prisons—in particular the transformations of the partnership between the Ministries of Justice and National Education—the article analyzes digital activities according to three distinct regimes: occasional institutional uses (videoconferences), regulated uses (computer stations without access to the Internet) and illicit but tolerated uses (mobile phones). This typology makes it possible to situate digital tools at different levels of pedagogical interaction: as vectors of institutional communication, as supported learning supports, or as informal resources for expression and socialization.

The SPOC in Prison project is a central field of study here. This experimental device is based on pedagogical engineering specifically designed for the prison context: disconnected digital modules, adapted scripting, navigation autonomy, self-evaluation activities, sobriety of interface design. These tools are used not only as technical supports, but as catalysts for educational interactions at several levels: individual support, mutual aid between peers, collective discussions about the content.

This approach highlights the way in which pedagogical engineering can promote the articulation between different forms of education in detention: formal education (structured and certifying knowledge), non-formal education (workshops, one-off training) and informal education (learning from experience and spontaneous interactions). At the heart of this articulation, human mediation appears essential, as does the learning of digital literacies—understood here as situated, critical and creative social skills.

Three critical dimensions emerge from this study: learning, which involves codified knowledge through filtered digital uses; mediation, which relies on the people involved in making this knowledge accessible and appropriate; and the aesthetics of resources, which questions the semiotic forms mobilized in a constrained technical and symbolic context. These dimensions are thought of in a dialogical way, i.e., in the logic of co-construction and mutual recognition.

The article concludes by formulating five lines of reflection: (1) pedagogical interactions as training levers; (2) the prison as a specific laboratory for educational digitization; (3) the design of devices adapted to heavy technical constraints; (4) the recognition of digital literacies as critical and situated skills; (5) the structuring role of human mediation in learning dynamics. It emerges that any educational transformation in detention must be anchored in a situated, reflective and participatory approach, attentive to actual practices and the conditions in which they emerge.

Keywords: pedagogical interaction; digital literacies; education in detention; educational engineering; constrained environment; mediation

Introduction

Prison is a penitentiary system that constrains multiple activities, institutionalizes interactions and that is based on partnership and experimental logic. In this article, we are particularly interested in the educational programs set up by the Ministry of National Education in French prisons: school education, training leading to qualifications or supervised workshops. These systems play a central role in access to knowledge, despite well-known structural and pedagogical limitations: discontinuity of learning pathways, heterogeneity of audiences, low autonomy of the systems, unequal access to resources and, above all, almost total absence of the Internet. This major digital constraint directs the systems towards specific technical solutions (disconnected tools, sober and secure media) and invites us to shift our gaze towards forms of learning that are often invisible by institutional grids. This learning, situated and relational, is built on a daily basis in speech, gesture, narrative or observation, and finds an extension or support in certain adapted digital uses. They are deployed in intermediary spaces of speech, ephemeral and shared between peers, which reflect a subjectivity specific to the prison environment (Alidières, 2025).

In order to examine the conditions of emergence, the forms and the challenges of digital educational practices in prison, we will start by setting out the institutional and historical framework of education in prison, before analyzing the objectives and contributions of the SPOC in Prison project. The next part will present the analytical framework and the andragogical avenues opened up by this experiment.

Presentation of the Study Framework

Education in prison cannot be understood as a simple service or a complementary activity: it is at the heart of a system of tensions between repressive logic, injunctions to reintegration, fundamental rights and material conditions of exercise.1 It is part of a long history of the prison as a system of control, moralization and, more recently, training, and is now part of a complex partnership between the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of National Education. This section aims to explore the historical foundations and contemporary transformations of the prison institution in France and the current forms of educational provision in detention, its implementation methods, its constraints and its evolution.

Institutional Context

Education in prison is part of the complex history of an institution marked by rationales that are both repressive and reintegrative. In Antiquity, prison was not a punishment, but a place of temporary detention, the penalties being mainly corporal and public. In the Middle Ages, confinement gained in importance with royal, ecclesiastical or seigniorial prisons, intended to maintain order. The modern prison was born in the seventeenth century, in a desire to discipline the social margins. In the eighteenth century, under the influence of the Enlightenment (Beccaria 2023), prison was thought of as a rational and proportionate sanction, intended to reform rather than punish. The 1810 Penal Code enshrined imprisonment as a benchmark for sanctions, supported by a standardized prison architecture.

Two models then structured the prison organization: the Pennsylvanian model, based on total isolation, and the Auburnian model, based on silent work. In France, preference was given to individual confinement (law of 1875). The twentieth century, punctuated by prison crises, saw the emergence of criticisms of the ineffectiveness of the repressive model, particularly through the mobilizations of the 1970s2 who denounced a system that generated recidivism rather than reintegration. These criticisms led to the creation of organization to control prisons—in particular the General Control of Places of Deprivation of Liberty—, the development of alternative sentences and increased attention to fundamental rights of those deprived of liberty.

In this context, the right to education for prisoners is being formalized. If, as early as the nineteenth century, religious or philanthropic initiatives provided basic education, it was in the twentieth century that a more formal framework was structured. In France, the 1987 reform enshrined access to education in detention as a right, governed by an agreement between the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of National Education. This framework allows for the assignment of tenured teachers in detention, the creation of prison classes and access to qualifying courses,3 often in partnership with the National Centre for Distance Learning (CNED). Specific initiatives such as the section for students with disabilities at the University of Paris 8 or the associations GENEPI4 and ALBIN provide additional support.

Today, about 30% of prisoners are enrolled in an educational activity, mainly in basic training (literacy, French as a foreign language, refresher courses), but also in diploma courses. Exam success rates, particularly in CAP/BEP,5 are high (up to 95%). However, the constraints of the prison environment (frequent transfers, unequal access to resources, strict supervision) severely limit the continuity of learning.

The introduction of digital technology in detention reconfigures these issues. For the past ten years, some schools have been equipping themselves with closed digital work environments (intranet without Internet access), and local platforms, like MoodleBox and PrisonCloud allow offline educational activities. However, unequal access, strict security regulations and low levels of equipment are holding back the deployment of these tools.

It is in this context that the European project SPOC in Prison is an attempt, still exploratory, to renew educational practices in detention. By mobilizing disconnected digital tools, it seeks to reconcile learners’ empowerment objectives with prison realities that are often not compatible with the usual pedagogical rationales. These tools are designed to allow very short training courses, understood here as learning sequences of a maximum of two days, but their implementation remains conditioned by strong logistical, technical and institutional constraints. Pedagogical engineering occupies an essential place, although it must continually deal with the narrow margins of the context: restricted access to resources, trade-offs between safety and learning, discontinuous temporalities, etc. Human support, accessibility of content and the diversification of forms of learning (formal, non-formal and informal) are thus thought of not as self-evident but as permanent challenges. Finally, far from proposing a generalizable model, this experiment questions public policies on education in detention on the basis of situated engineering, dependent on real uses, local dynamics and empirical adjustments rather than on rational planning.

Presentation of the Project

The SPOC in Prison project is a European project funded by the Erasmus+ program aimed at developing digital modules for non-connected training, adapted to the constraints of the prison environment. In concrete terms, the system is based on a series of educational content embedded on secure tablets or computers on a closed local network (without access to the Internet). This content is modular, scripted, accompanied by interactive activities and designed to promote self-learning while maintaining human mediation.

Each module covers basic skills—written expression, logical reasoning, digital skills—and offers self-assessment exercises, explanatory videos, as well as pedagogical guidance by a trainer or teacher present on the prison site. The implementation in the partner institutions involved a test phase, user feedback, and adjustments according to local constraints (time, space, security, equipment).

Description of the SPOC in Prison Experimental Devices

One of the significant contributions of the SPOC in Prison project lies in its ability to articulate, in a single system, the three main forms of education identified by Gallacher and Feutrie (2003) and Maulini and Montandon (2005): formal, non-formal and informal. In a context where learning paths are often fragmented and unstable, this modular approach introduces a form of continuity while adapting to the diversity of profiles and situations.

The modules can be used from a formal perspective, in support of qualifying courses (refresher courses, preparation for the CAP or the baccalaureate) in accordance with the objectives of the National Education. They can also be integrated into non-formal uses, supervised by speakers—teachers, trainers, mediators—who adapt them to the local context, use them in workshops or group sessions. Finally, their ergonomic structure favours informal use: in cells or activity rooms, prisoners can access them independently, according to their needs and desires, thus stimulating self-training or cooperation between peers.

In an environment as constrained as prison, where learning opportunities are numerous but discontinuous and often in tension with institutional rationales, this articulation is neither obvious nor linear. It presupposes a flexible pedagogical engineering, attentive to real uses, prison temporalities and available resources. SPOC in Prison does not propose a standardized model, but a situated experiment that highlights the possible articulations between compartmentalized forms of education, while questioning the concrete conditions of their implementation.

This versatility makes the system particularly suited to the variability of the profiles, rhythms and expectations of inmates. It is based on a set of scripted modules on various subjects of general knowledge, and aimed at the acquisition of digital knowledge and skills. By operating offline, it circumvents the widespread lack of Internet access in prisons. This choice responds to a central constraint: the strict control of the use of digital technologies in detention, historically marked by institutional mistrust. The first experiments with disconnected tools for educational purposes, such as Virtual Campus in the United Kingdom in the 1990s, bear witness to this tension between innovation and regulation.

The main interest of this system lies in its ability to adapt to the temporal and organizational constraints specific to the prison environment. The lack of connection, the discontinuity of detention pathways and the restricted modalities of participation require great flexibility in educational formats. Designed in the logic of non-formal education, the system also allows the emergence of informal practices, in particular thanks to the involvement of non-specialist speakers who accompany the participants in a dynamic of mediation and co-construction of knowledge.

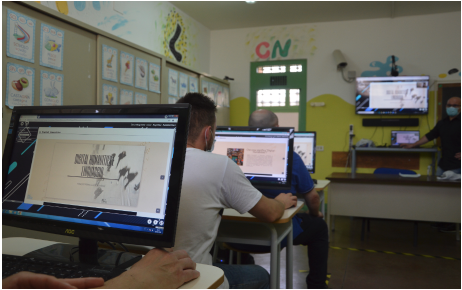

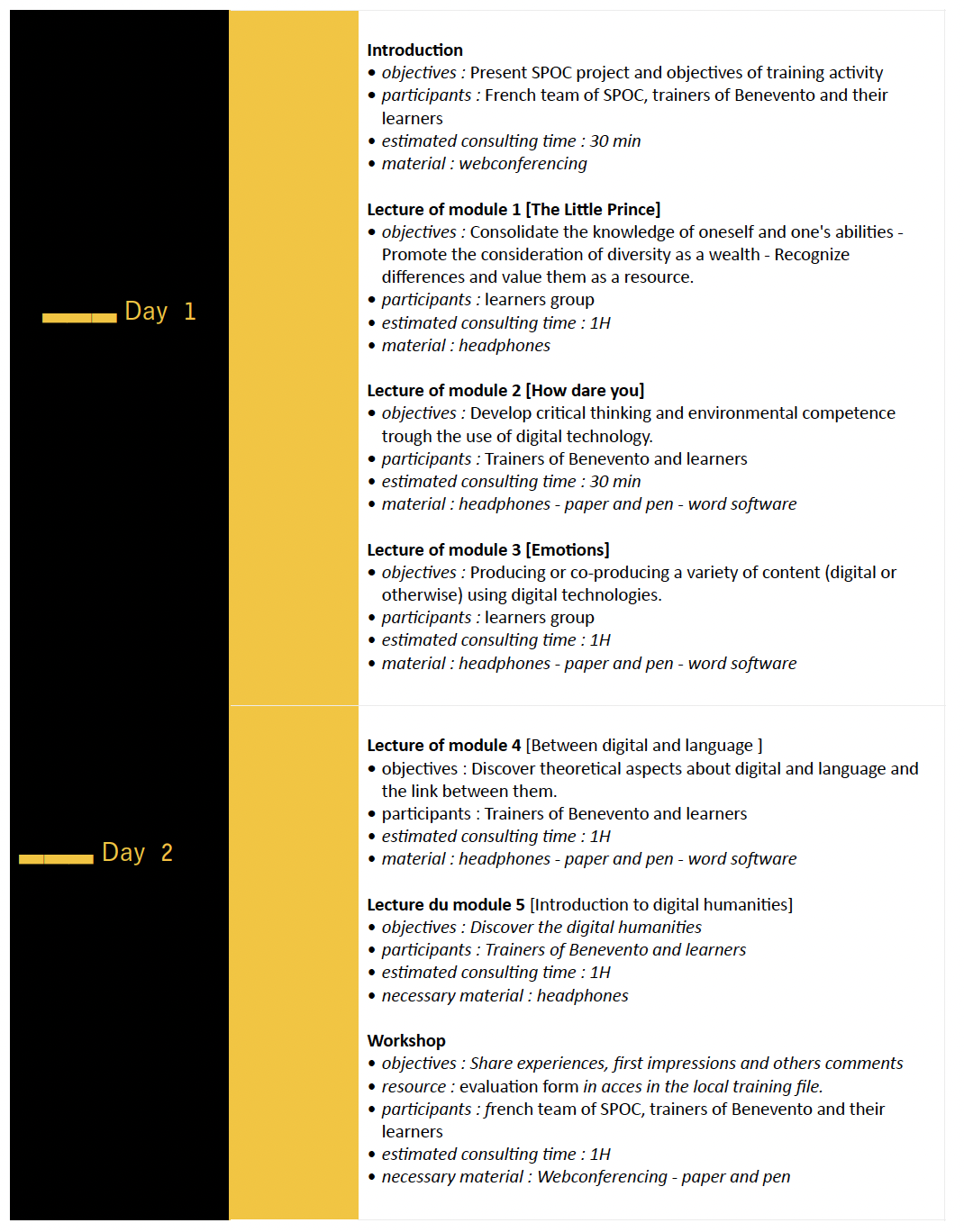

The experiment conducted at Benevento Prison (see image 1) took place over two days of training granted by the prison administration (see image 2).

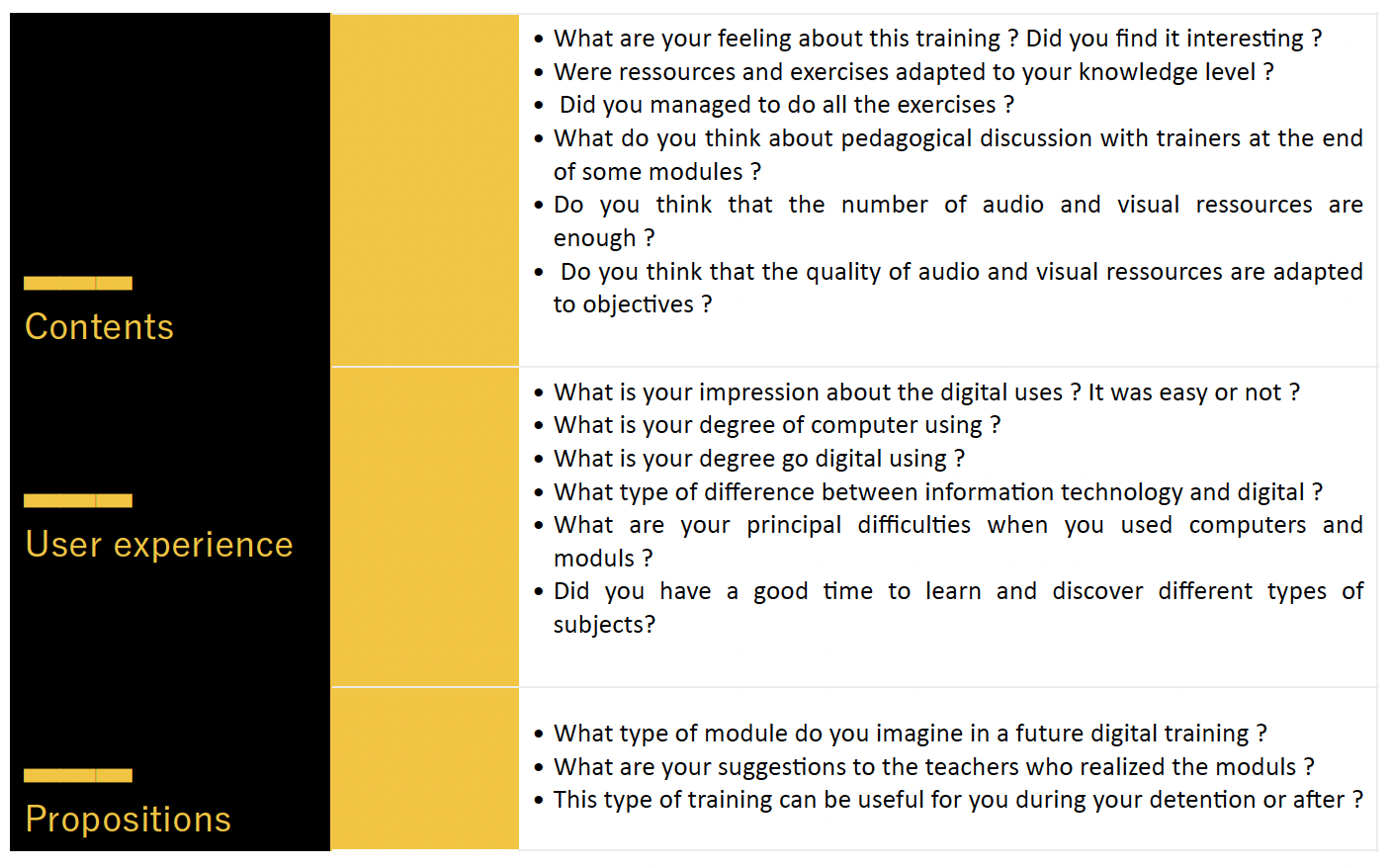

At the end of the meeting, a questionnaire (see image 3) was offered to the detainees. It was based on three axes: content, user experience and prospects for improvement. It aimed to collect impressions on the pedagogical relevance of the modules, the way in which the participants appropriated the tools in a constrained environment, as well as the difficulties encountered and the levers of engagement. Particular attention was paid to the suggestions made, in a participatory logic oriented towards the continuous adaptation of the system to the needs expressed.

The modules,6 hosted on workstations without connection, were scripted to offer an autonomous pedagogical progression. They addressed various themes: digital document management, word processing, content production, but also critical reflection on public figures (Greta Thunberg) or cultural works (such as The Little Prince). The goal was to offer accessible, stimulating content adapted to the heterogeneity of the participants’ educational backgrounds, digital skills and motivations.

The navigation, designed to be intuitive, included interactive activities (quizzes, reformulations, concept maps) and allowed great flexibility of use: the modules could be followed individually or collectively, with or without accompaniment.

The deployment of the project remains conditioned by several factors: institutional acceptance, training of educational teams, availability of equipment, posture of prison management. The feedback underlines an added value in terms of motivation, a feeling of competence and diversification of media, but also reminds us of the importance of strong human support. In the absence of the latter, digital technology risks becoming a simple substitute for an insufficient pedagogical presence.

Digital Uses and Literacy

The prison environment is characterized by an ambivalent relationship with digital technologies, oscillating between strict regulation, supervised openings and more or less tolerated informal practices. In this particular configuration, it is possible to distinguish three levels of technological use that structure the relationship to digital technology and communication with the outside world differently: punctual-institutional, regulated-programmed, illicit-tolerated. They often coexist within the same establishment and are part of heterogeneous local ecologies, shaped by prison policies, the profiles of incarcerated people, and the intermediation methods provided by professionals (teachers, trainers, cultural workers, etc.).

Institutional Uses and Controlled Technicalization

Videoconferencing devices illustrate a punctual and highly regulated use of technology. Initially introduced for judicial purposes (in particular to hold hearings remotely), videoconferencing has gradually been extended to other uses: medical appointments, interviews with administrative services, and even online family visits. But these uses remain exceptional, triggered and regulated by the institution. They reveal a controlled technologization of social interactions, limited to defined contexts, precise temporalities, and prescribed purposes.

Regulated Uses: Supervised Learning and Limited Access

A second level of use concerns access to computer workstations without connection, whether fixed (in the activity room) or portable (in the cell). These devices are accompanied by strict regulations regarding authorized content, accessible software, and the use of removable media. While they allow for certain learning or educational approaches, these tools remain unevenly deployed depending on the establishment, and their effectiveness depends largely on the human support and prior digital skills of detainees. This regime thus reveals profound inequalities of access, mediation, and appropriation.

Informal Uses: Constrained Autonomy and Grey Areas

At the opposite end of the spectrum, mobile phones circulate clandestinely in many establishments. Despite their official prohibition, they play an essential social and communication role: maintaining family ties, access to information, moral support, etc. These uses reflect a strong demand for digital autonomy, to which institutional arrangements only partially respond. They draw a grey area of the prison’s digital environment, where informal practices satisfy the basic needs of inmates.

Digital Literacy Under Constraint

In this context, digital literacies—defined as the technical, critical and creative skills mobilized in the use of technologies (Buckingham, 2021; Barton & Hamilton, 1998)—take on a specific meaning in detention. They develop under duress, by trial and error, mutual aid, observation, or circumvention of the rules and reveal forms of differentiated participation, conditioned by the regimes of access, the mediations available and the institutional resources.

Towards a Sociotechnical Reading of Asymmetries

These material and institutional differences lead to the questioning of the notion of interactional symmetry: who actually has the means to speak, to access the tools, to interact in conditions of recognition? This question, at the crossroads of interactional analysis and the sociology of technologies and innovations, engages a broader reflection on the rights of use and the forms of authorization to learn or communicate in detention.

Several technologized educational devices are currently being tested (Alidières and Abbadie, forthcoming). All of them come up against recurring obstacles: access limitations, rigidity of formats, difficulties of coordination between educational and prison actors. However, they also pave the way for a reconfiguration of pedagogical relationships in a constrained environment. The challenge is not only the introduction of materials, but the redefinition of the conditions of learning and participation in contexts of restriction, surveillance and fragmentation of pathways.

Faced with the differentiated regimes of access to digital technology in detention and the inequalities they generate, the central question is that of pedagogical engineering. It is not only a question of adapting existing content to technical and institutional constraints, but also of designing educational systems based on available resources, real uses and the situated knowledge of prisoners. In this perspective, the experiments carried out, in particular the SPOC in Prison Project, appear as attempts to build technologized learning environments sensitive to constrained contexts and the interactional dynamics that run through them. The system developed is based on a modular scripting of content, a simplified interface, self-assessment activities, and constant support for human mediation. It has been designed according to three complementary axes:

- the implementation of short training courses focused on general knowledge and fundamental digital skills;

- the training of speakers in pedagogical scripting in a constrained context;

- in situ experimentation with a group of inmates, based on a course co-constructed with the trainers involved in the project.

This approach makes it possible to articulate several dimensions: structured and accessible content, taking into account the heterogeneity of profiles, and above all attention to real-world uses and situated forms of learning. It is thus in line with analyses that underline the central role of experiential knowledge developed in detention, whether from the point of view of detainees (Salane, 2018) or education professionals confronted with an unstable and little-recognized environment (Milly, 2004).

Pedagogical engineering then becomes a strategic lever: to compensate for breaks in the learning pathway, to circumvent institutional blockages, but also and above all, to support a dialogical posture in the educational relationship. It is not only a question of transmitting knowledge, but of co-constructing the conditions for its emergence in a space where educational, security and institutional rationales are sometimes in tension. This stance is in line with critical pedagogies (De Loye, 1975; Giroux, 2010) and participatory methodologies (Becquet, 2021), which give a central place to learners’ words, experiences and ability to act, including in highly regulated contexts.

Finally, such an approach calls for a systemic reading of the act of teaching in prison: the pedagogical dimensions cannot be dissociated from public policies, the professional cultures present, or the power relations that structure each institution. Designing an adapted pedagogical engineering thus amounts to taking a political look at the conditions of access to education, in prison as elsewhere, assuming that any pedagogical device is also a space for negotiation, recognition or exclusion.

By resituating pedagogical design in its material, institutional and relational environment, this section has highlighted the complexity of educational work in detention. It remains to be understood how these mechanisms, however well thought out they may be, are actually invested, interpreted, and negotiated the real world. The third and final part thus focuses on analyzing educational interactions in a prison context, through a situated approach based on extracts from a corpus of audiovisual data. The goal will be to highlight the forms of interactional adjustment, the dynamics of commitment, but also the discreet gestures of resistance, circumvention or cooperation, which give substance to the educational activity on a daily basis.

Observing Educational Interactions: A Situated Approach

In this final portion of the article, we propose an analysis of educational interactions in detention, based on a situated position derived from the sciences of language. The aim is to examine how learning takes shape within specific pedagogical configurations, taking into account institutional constraints, the digital media mobilized and the forms of engagement of the actors.

Four entries structure this analysis:

- the methodological principles of the interactional approach;

- the interactional phenomena observed in the corpus;

- contrasting learning scenes (formal, non-formal, informal);

- the place of pedagogical scripting and “web design” in the architecture of the educational experience.

An Interactional and Situated Approach

Interactional analysis considers language exchanges as situated social practices. It postulates that participants have ordinary skills to interpret their environment and organize their activity, even in a constrained context. Observing educational interactions in detention therefore amounts to analyzing not only what is said, but what is done with language, gestures, looks and objects.

This inductive approach, attentive to detail, makes it possible to grasp the granularity of practices: a reformulation, a hesitant instruction, a look, a moment of silence, discreet help between peers. These microphenomena carry major educational and relational issues, particularly in a context marked by statutory asymmetries and implicit rules of expression. They give access to a situated linguistic action, which deserves to be recognized, interpreted, transmitted.

In a prison context, this critical and situated stance also engages a reflection on the forms of control of speech (supervised speech, restricted lexicons, limited access to media). Interactional analysis then becomes a lever for questioning the conditions of participation, the margins of negotiation and the dynamics of recognition in closed learning environments. It does not claim to be exhaustive, but aims to shed light on local adjustments, tensions and forms of cooperation made visible in interactions.

Corpus of Interactional Phenomena

The corpus collected in the framework of the SPOC in Prison project constitutes the empirical basis of our analysis. It includes about 15 hours of audio and video recordings, from educational sessions in two prisons (one in France, one in Italy), as well as ethnographic observations and informal interviews with the speakers.

The documented sessions include disconnected digital workshops, general knowledge modules, writing activities, as well as spontaneous exchanges outside of formal training times. This diversity of contexts makes it possible to observe a set of interactional phenomena revealing the pedagogical dynamics in detention:

- peer-to-peer reformulations to ensure that a numerical instruction is understood;

- alternating glances between a trainer and the screen to discreetly ask for help;

- prolonged silences, interpreted as markers of hesitation, embarrassment or self-censorship;

- gestures of mutual support, such as showing where to click, exchanging a word of encouragement.

These elements, often absent from standardized analysis grids, testify to the collective mobilization of practical intelligence, at the heart of the learning experience. They show that, even in a constrained environment, interactions carry situated knowledge.

Three Contrasting Educational Scenes

We have identified three educational situations from our corpus which are presented in succession, each accompanied by a representative visual diagram: the first shows a structured exchange between a teacher and two inmates in a history module (formal education); the second, a writing workshop where the word circulates freely between the participants (non-formal education); the third, an informal conversation about problems that arose in detention in a common room, giving rise to a spontaneous conversation (informal education). These scenes, although different in their modalities, illustrate the continuity of learning through multiple formats and interactions.

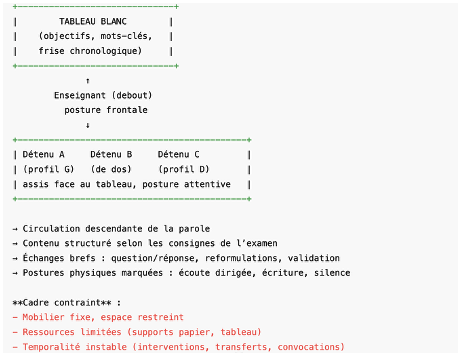

Scene 1: Formal Learning—A History Lesson (Image 4)

This image illustrates the institutional and normative framework of learning in prison. The teacher, positioned in front of a whiteboard, structures the session around specific educational objectives: to transmit knowledge, develop skills and prepare the inmates for the examination for the college certificate which certifies the end of the school curriculum with the entry into high school.

This type of situation, similar to a traditional classroom, is based on a top-down and supervised approach. The interactions between the teacher and the inmates focus on the clarification of the content and the methodical progress towards certifying objectives. However, in a prison environment, these classroom sessions are often influenced by specific constraints: a temporality fragmented by institutional obligations and limited access to educational resources.

Figure 1 is inspired by the real layout observed during a history lesson. The teacher organizes the space around a central whiteboard, on which the day’s objectives are noted. The detainees are placed in front of him in a frontal position, characteristic of traditional school forms. Exchanges remain mainly focused on the transmission of content, although moments of clarification or reformulation can introduce interactional micro-adjustments.

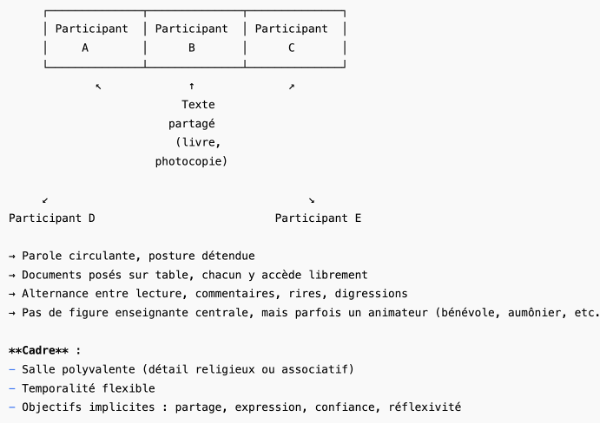

Scene 2: Non-Formal Education—Reading Workshop (Image 5)

Non-formal education, illustrated by a collective reading and text analysis session, offers a different approach. In this situation, the participants are gathered around a table, engaging in a more horizontal and collaborative dynamic.

This scene takes place in a space set up as a room for cultural or religious activities. The participants are seated around a table in a circular layout, conducive to the co-construction of meaning. This provision promotes the emergence of a climate of trust, mutual aid and reflective exchanges, in a flexible, non-hierarchical educational framework, outside school standards.

These workshops aim to develop specific skills, in this case critical reading and interpretation, while offering a space for dialogue and exchange. This type of education, although less regulated than formal education, is still structured around explicit pedagogical objectives. It allows work on transversal dimensions, such as oral expression, self-confidence or the ability to argue.

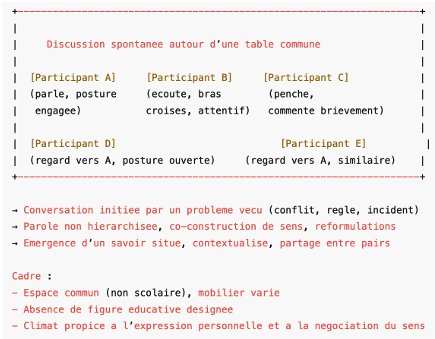

Scene 3: Informal Education—Spontaneous Discussion (Image 6)

Informal education manifests itself in spontaneous moments of interaction, such as the discussion between a teacher and inmates, captured in the image below.

This discussion is initiated by the detainees about problems that have arisen in detention with the teacher on the left of the image. It allows to expose problems and sometimes find resources to resolve them. It is not directly structured around a specific content or pedagogical objective, but this discussion gathers forms of experiential knowledge (Breton, 2020) and gives rise to situated learning.

These interactions play a fundamental role in prisons. They allow inmates to integrate practical and social knowledge adapted to their context. For example, discussing current events or a situation experienced in detention can become an excuse to work on skills such as critical analysis or communication. The teacher, as a mediator, accompanies these learning methods by valuing active participation and individual contributions.

Pedagogical Device and Scripting: A Situated Engineering

The analysis of interactions cannot be dissociated from the pedagogical scripting and the design of the media. In the SPOC in Prison project, two issues were particularly decisive: the structuring of the content and human mediation. The modules were designed on the basis of thematic sequences, explicit objectives, and time for appropriation, production and synthesis. The lack of an Internet connection has imposed a disconnected but interactive format, integrating quizzes, reformulations and self-assessments. This modularity met a double requirement: to allow individualized progress despite discontinuous temporalities, and to promote autonomous commitment, without resorting to normative evaluation.

The Educational Experience in the Context of the SPOC in Prison Project

The analysis of educational interactions in detention cannot ignore the concrete conditions of the learning experience. In the framework of the SPOC in Prison project, three interdependent dimensions have been identified as particularly structuring: learning, mediation and the aesthetics of the resource. These dimensions draw a critical map of what it means to “learn” in a highly constrained environment.

- Learning: This is access to digital literacy within a prescribed framework, often filtered and not very customizable. Learning is not just about acquiring technical skills; it implies a confrontation with a codified digital culture, the appropriation of which is unevenly distributed. The interfaces, which are not well adapted to the profiles of the prisoners, represent an additional difficulty in the engagement of learners.

- Mediation: Human support is essential, although weakened. The role of the teacher is central, but subject to strong institutional constraints: precarious status, lack of specific training, overload of tasks. The teacher becomes a go-between (Chantraine, 2003), a key player in opening up spaces for dialogue, mutual understanding and the revaluation of knowledge.

- Aesthetics of the resource: The semiotic forms mobilized (texts, images, videos, sounds) can offer diversified and engaging paths. However, the materiality of the media (restricted tablets, lack of network) and the lack of institutional recognition of these productions limit their scope. What is perceived as expressive or creative is not always legitimized as educational.

Design and Accessibility: From Constraint to Resource

In this context, design is not a secondary dressing: it is a structuring element of the educational experience. The interface developed in SPOC in Prison has been designed according to the principles of sobriety, intuitiveness and robustness, in order to be compatible with limited media (restricted workstations, secure tablets, absence of network). The choice of design met a double requirement:

- Accessibility: allow audiences who are not familiar with digital environments to easily navigate through the modules;

- Pedagogical coherence: organizing content in a logical, readable and engaging way, despite the imposed linearity.

The hierarchical structure is deliberately restricted, without hyperlinks or notifications, to limit errors and dispersion. This constraint then becomes a pedagogical resource: it focuses attention on the essential, promotes in-depth study and makes the experience more readable. Each module integrates significant visual and textual elements, designed to establish a symbolic link with the outside world (public figures, cultural references), while valuing the participation of learners.

Scripting at the Heart of the Learning Experience

The pedagogical scripting is the basis of the engineering developed in the project. It was not a question of offering fixed content, but rather of building learning paths that were modular, flexible, meaningful and adapted to prison temporalities.

- Clarity and autonomy: the modules are structured around thematic sequences including an introduction, moments of appropriation (reading, visualization), production (writing, reformulation) and reflection (self-evaluation, synthesis). The whole aim is to strengthen the participants’ ability to find their way around, to actively engage and to evaluate themselves without resorting to normative devices.

- Personalized progression: modularity allows everyone to build their own path, according to their needs, rhythms and preferences. Interactive activities (quizzes, interim assessments, deferred feedback) punctuate the courses and support engagement.

Scripting has been designed as a dynamic device, where educational content, human interactions and technical constraints are articulated to bring out situated, reflective and potentially transformative learning experiences.

Conclusion

This work was part of a double perspective: to understand the forms of pedagogical interaction in prison and to explore the conditions of implementation of digital devices in a constrained environment. From this focus, five lines of reflection emerged, corresponding to the five fundamental dimensions of the educational experience analyzed. Pedagogical interactions, whether in formal education, non-formal workshops or informal conversations, are the dynamic core of learning in detention. They are the place where contents, postures, roles and knowledge are negotiated and form a space for the co-production of meanings and mutual recognition, which is particularly valuable in a context of biographical and social rupture. Thinking about training in prisons therefore means first thinking about the interactional formats that make them possible.

Prison, as an institutional space marked by confinement, regulation and hierarchy, imposes major constraints on the use of digital technologies. However, it is precisely in this context that digital training can take shape provided that it is designed from the field, in connection with real needs, conditions of use and local ecologies. Prison is not a “non-digital” but a “digital other,” where uses, even limited or diverted, reveal situated forms of appropriation, indicators of needs and practices that are invisible.

The experimentation of the SPOC in Prison system has demonstrated the feasibility and relevance of disconnected digital devices, designed specifically for prisoners. These formats require rigorous pedagogical engineering, based on scripting, ease of use, the autonomy of learners and the anticipation of technical contexts. Digital without connection is not digital on the cheap: it is a contextually relevant digital technology, which can become a lever for transformation provided that the logic of exclusion or standardization is not reproduced.

Beyond access to tools, it is digital literacies understood as social, critical and creative practices, that give meaning to the educational uses of digital technology. Designing resources with this in mind implies taking into account the skills actually mobilized by learners: navigating, understanding, creating, dialoguing. It also implies recognizing the invisible forms of learning, the implicit knowledge, the reflexive detours that even the most rudimentary digital tools allow.

Finally, any educational transformation in detention depends on the actors who bring it to life. Prisoners, of course, but also people working in educational, cultural or associative settings, who mediate between tools, content and situations. This mediation is pedagogical, technical, but also symbolic: it legitimizes knowledge, it opens up spaces for expression, it makes reflexivity possible. In an environment where speech is regulated, mediation becomes a form of pedagogical resistance, a way of rehumanizing the devices.

References

- Alidières, L. (2025). Une intersubjectivité du carcéral ? Dans L. Rebout (dir.), Comment construire une subjectivité carcérale : un chercheur en prison. Phaneres.

- Alidières, L. et Abbadie, A. (à paraître). La prison à l’ère numérique. Université Tous Terrains.

- Barton, D. et Hamilton, M. (1998). Local literacies: Reading and writing in one community. Routledge.

- Beccaria, C. (2023). Des délits et des peines (traduit de l’italien par M. Chevallier). Flammarion.

- Becquet, V. (dir.). (2021). Des professionnels pour les jeunes : Sociologie d’un monde fragmenté. Champ social éditions.

- Bréant, H. et Contini, L. (2024). L’école en prison. Conditions d’enseignement et expériences scolaires des mineurs détenus (Synthèse du rapport de recherche). Ministère de la Justice, Pôle recherche de la Direction de la protection judiciaire de la jeunesse (DPJJ).

- Breton, H. (2020). Narration du vécu et savoirs expérientiels. Éducation permanente, 222, 5-10.

- Buckingham, D. (2021). The media education manifesto (2e éd.). Polity Press.

- Chantraine, G. (2003). Prison, Désaffiliation, Stigmates. L’engrenage carcéral de l’« inutile au monde » contemporain. Déviance et Société, 27(4), 363-387. https://doi.org/10.3917/ds.274.0363

- De Loye, P. (1975). Freire (Paulo). Pédagogie des opprimés suivi de Conscientisation et révolution (trad. du brésilien). Revue française de pédagogie, 30, 62-64.

- Giroux, H. A. (2010). On Critical Pedagogy. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Maulini, O. et Montandon, C. (2005). Le triangle pédagogique : Interactions entre savoirs, élèves et enseignants. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Milly, B. (2004). L’enseignement en prison : du poids des contraintes pénitentiaires à l’éclatement des logiques professionnelles. Administration et Éducation, 104(4), 77-85.

- Rebout, L. (dir.). (2025). Comment construire une subjectivité carcérale : Un chercheur en prison. Éditions Phanères.

- Salane, F. (2018). Être étudiant en prison. L’évasion par le haut. Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Notes

- This expression refers to all the physical, logistical and organizational constraints that govern teaching in prison: availability of rooms, access to teaching materials, presence or absence of digital equipment, secure management of time and travel, etc. ↩︎

- Michel Foucault, Jean-Marie Domenach and Pierre Vidal-Naquet founded the Groupe d’information sur les prisons (GIP) on February 8, 1971. ↩︎

- The Certificate of Professional Aptitude [Certificat d’aptitude professionnelle] (CAP), the Certificate of Vocational Studies [Brevet d’études professionnelles] (BEP) or the baccalaureate [baccalauréat]. These diplomas correspond to the end of middle or high school in the French education system. ↩︎

- Groupement étudiant national d’enseignement aux personnes incarcérées (National Student Group for the Teaching of Incarcerated Persons) (Note from the editors: GENEPI was dissolved in 2021). ↩︎

- See note 3. ↩︎

- All modules are available at: https://www.univ-montp3.fr/fr/international/coop%C3%A9ration-internationale/projets-europ%C3%A9ens-et-internationaux/projet-spoc ↩︎

Author

Lucie Alidières

Senior lecturer in language sciences

Research unit LHUMAIN

University of Montpellier Paul-Valéry

lucie.alidieres@univ-montp3.fr

Cite this article

Alidières, L. (2025). Learning in Detention: Pedagogical Interactions and Digital Literacy in a Constrained Environment. Apprendre + Agir, special issue 2025, Learning and Transforming: International Practices and Perspectives on Prison Education. https://icea-apprendreagir.ca/learning-in-detention-pedagogical-interactions-and-digital-literacy-in-a-constrained-environment/