Special Issue 2025 of Apprendre + Agir

Paul Draus

Anna Müller

Abstract

This paper reflects on the “Art & Agency” workshops that were conducted at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, which used various forms of creative practice and dialogic methods inspired by the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program to engage diverse communities in conversations about creativity, empathy and transformation. Through visual art, performance, and storytelling, participants explored themes of connection, joy, healing, recovery, resilience, and neighborhood. The workshops were facilitated by formerly incarcerated men and women and fostered inclusive dialogue, breaking down barriers between and within communities, highlighting art’s potential as a tool for personal and collective empowerment.

Keywords: art, agency, prison education, community-based practice, participatory pedagogy

Introduction: Three Initiatives Linking Art, Education, and Formerly Incarcerated Communities

Over the past several years, the University of Michigan-Dearborn has become the setting for a series of dynamic initiatives that bridge the worlds of incarceration and freedom, employing creative practice to transform how we engage with issues of justice, identity, and community. This article examines the evolution and interconnections among three such efforts: the ‘Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program’ (IO), the ‘Art & Agency’ (AA) workshops, and the ‘Who’s Your Neighbor?’ workshops. Each initiative brings together incarcerated or formerly incarcerated individuals, university students, artists, and community members in pursuit of more humane and inclusive forms of education and dialogue.

First, the ‘Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program’ (IO) established a foundation for transformative pedagogy by facilitating collaborative classes inside Michigan correctional facilities. Bringing students “inside” the prison environment alongside currently incarcerated individuals, IO fostered co-learning, empathy, and critical reflection on systems of incarceration. Building on these foundations, the ‘Art & Agency’ (AA) workshops emerged as a post-pandemic response that shifted the focus from prison-based to community-based practice. Led collaboratively by formerly incarcerated facilitators and professional artists, AA workshops use creative modalities—visual art, poetry, movement, and performance—to explore themes of resilience, healing, and social belonging outside the carceral setting. Finally, the ‘Who’s Your Neighbor?’ (WYN) series represents the most recent phase, taking the collaborative AA model into public spaces across Detroit. These workshops, co-developed and facilitated by formerly incarcerated alumni from IO, use the arts to provoke crucial conversations about inclusion, difference, and what it means to build community after incarceration.

To provide readers with clear orientation, the article has been structured in chronological order to show the evolution of our initiatives over time. The first section provides necessary background on IO,discussing its history, structure, and transformative impact at our university, including the creation of the Theory Group (TG)—a collective of IO alumni supporting ongoing education and engagement–-and the changes to the initiative as a response to the restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic. The second section describes the creation of AA out of IO as we moved from a traditional classroom-type setting to a community-based practice. Here, we trace the genesis and development of AA, examining its foundations in IO theory and its role in using creative, dialogic methods to humanize experiences of incarceration and social exclusion. The section highlights the workshop facilitation by formerly incarcerated individuals and the emergence of shared creative practice as a vehicle for personal and collective transformation. This leads to a discussion of WYN, an initiative that stemmed from AA workshops and extended creative dialogue across communities. This third section moves us beyond the university campus, detailing the themes and outcomes of public-facing, art-based gatherings designed to deepen reflections on community, identity, and belonging—particularly for those impacted by the justice system. In the fourth section, we return to the prison, integrating new approaches developed within AA and WYN in correctional settings. We describe efforts to bring those creative, arts-based methods back inside correctional facilities, detailing new pedagogical experiments and cross-border collaborations.

In our discussion section, we offer some pedagogical reflections and theoretical perspectives on the evolution of our initiatives, synthesizing lessons learned across all three enterprises. The discussion situates our practices in broader conversations about education, agency, the role of creativity under constraint, and the disruption of conventional boundaries in learning. Finally, in our conclusion, we offer some future directions for this practice, summarizing key takeaways concerning the value of collaborative and creative pedagogy, reflections from participants, and plans for sustaining and expanding this work—including more rigorous evaluation and the building of a flexible, adaptable curriculum that bridges prison, classroom and community, building connection and defying physical, social and conceptual confinement. By tracing the interrelated trajectories of IO, AA, and WYN, this article aims to illuminate how arts-based participatory practices — led by those most affected by incarceration — can challenge boundaries, foster empathy, and seed community transformation inside and beyond the walls of prisons.

The Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program (IO) and the Theory Group (TG): From Prison-based Classes to Creative Practice

The Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program (IO), founded in Philadelphia, PA, in 1997, had a long history at the University of Michigan-Dearborn (UMD), thanks in large part to the pioneering efforts of Professor Lora Lempert, who led the first class in a Michigan prison in Fall 2007. IO is a distinctive pedagogical model that brings university (“Outside”) students together with incarcerated (“Inside”) students in a semester-long series of dialogue-based sessions. Designed to humanize both “Inside” and “Outside” participants, IO also involves exploring academic topics and engaging in structure reflections and project-based learning. The success of this course over the next decade and a half not only laid the foundation for future IO classes across the state but also helped inspire the creation of the Theory Group (TG), a group of IO alumni that consists of inside and outside members who help guide the program and design educational events (Draus and Lempert, 2013).

Despite persistent challenges in navigating the delicate balance between the demands of prison administration and the shifting priorities of the university, the IO faculty and the TG were in a relatively strong position at UM-Dearborn by 2019, keeping a stable relationship with the Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC), organizing numerous conferences and workshops, and training new IO faculty from across the country and the world. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic gave a serious blow to the program. Classes were suspended, contact with incarcerated TG members was abruptly cut off, and in-person IO instructor training ceased nationwide. Amid the fear and uncertainty, we sought to maintain connection, for example, by sending books to prison and sharing written responses to the readings; something we had done in our regular pre-Covid meetings. We occasionally would gain some news about the inside members from released individuals. Still, the sense of community we had built felt fragile, and efforts to sustain it were limited and strained.

In Fall 2020, as prison-based classes remained suspended due to the pandemic, Paul Draus introduced the idea of inviting formerly incarcerated alumni of the IO program to serve as “guest professors” in Zoom sessions with university students. It was a creative response to circumstantial limitations and offered a meaningful way to sustain the spirit of the program, as captured in the slogan, “Examining social issues through the prism of prison.” The class met virtually once a week for three-hour sessions, during which Draus and the guest professors (among others, Bryan Jones, Jemal Tipton, Kyle Daniel Bey, Chris Delgado and Lynn McNeal) led icebreakers and exercises adapted from the in-person IO format. This offered students an engaging experience, connecting people to each other while everyone was experiencing a new form of confinement due to the pandemic. It also marked a thoughtful step toward reimagining how IO could continue under changing circumstances. As with the in-person IO classroom, the virtual meetings sought to foster Paulo Freire’s (1970, 2000) ideal learning space—one in which authority was shared, and the boundaries between teacher and student blurred.

In Winter 2022, our campus cautiously reopened and the IO program changed its shape once again, as we could now meet in-person but the prison remained closed to volunteers. Thankfully, however, our group of formerly incarcerated guest professors continued to grow, and we benefited from the steady presence of Penny Kane, Bryan Jones, Kyle Bey, Lynn McNeal, Tamir (T-MAC) Bell, and Jemal Tipton—as well as others who joined for select sessions. We also counted with the support of Lacino Hamilton, an exonerated author and ardent prison abolitionist1 who argued that the dehumanization of prison was simply a wrong compounding a wrong, and Darryl Woods, who was later appointed a Police Commissioner in Detroit and advocated productive cooperation between law enforcement and community.2 Their insights and lived experiences added depth and immediacy to the discussions, shaping the rhythm of the class and challenging students to confront the moral and systemic dimensions of incarceration not as distant abstractions, but as urgent realities woven into the fabric of American society.

Rather than utilizing content dealing primarily with American mass incarceration, as is often the case in IO, we structured the class around the endurance of the human spirit in the face of dehumanizing systems, placing American mass incarceration in dialogue with historical experiences such as Nazi concentration camps and Soviet Gulags, with a focus on art produced in these conditions. We drew on a range of historical, sociological and theoretical texts, including Michael Ignatieff’s A Just Measure of Pain (1978), Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1977), Tadeusz Borowski’s Here in Our Auschwitz and Other Stories (1946), Territories of Terror by Svetlana Boym (2007), as well as classic writings by Henry David Thoreau, Clarence Darrow, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X. The course began by asking students to select an entry/reflection/story from the Hamilton American Prison Writing Archive to read and discuss. We invited deep ethical and historical reflection on the experience of incarceration and its relationship to creative and political resistance, while also navigating uncertainties of the post-pandemic moment.

We also maintained contact with the “inside”, still incarcerated members of TG, including Big Tone, Julio, Cowboy, Q, Bantu, Tyrone, Justin, Mario, Jay, and Steve X. From the outset, we hoped to foster a dialogue between the inside and outside participants by sharing class prompts and inviting responses from both groups. For example, we asked everyone to write a short poem in response to the question: “Who am I?” Below are some examples of the first poems written in response to that prompt, which helped reduce the gulf between “inside” and “outside” by highlighting each person’s distinctive sense of themselves, rather than their social position.

I am a time bender

Suspended in a space

Without air… reachingI am written words

decoding decades of generational

HurtI am a shape shape shifter

Constantly evolving in the

midst of darknessI am the sound of wind

singing the blues through

a family of treesI am the song playing in

the car next to you

The shift from a class focused primarily on prisons and their impact to one that centered on art and creative practice as a means of resisting oppressive conditions and reimagining social relations marked the beginning of a new way of doing these collaborative workshops. In witnessing how works of art facilitated conversations between students and guest professors, the class revealed something many educators already know: the profound connection between expression and action, particularly within systems of oppression and constraint. These conversations often moved beyond the course material and the context of incarceration, touching upon broader themes of human dignity, freedom, and the relationship between the individual and the collective. Students also had the opportunity to learn from formerly incarcerated guest professors how art can function to reclaim meaning, assert identity, challenge systems, and reflect on shared humanity—even in the face of dehumanizing conditions.

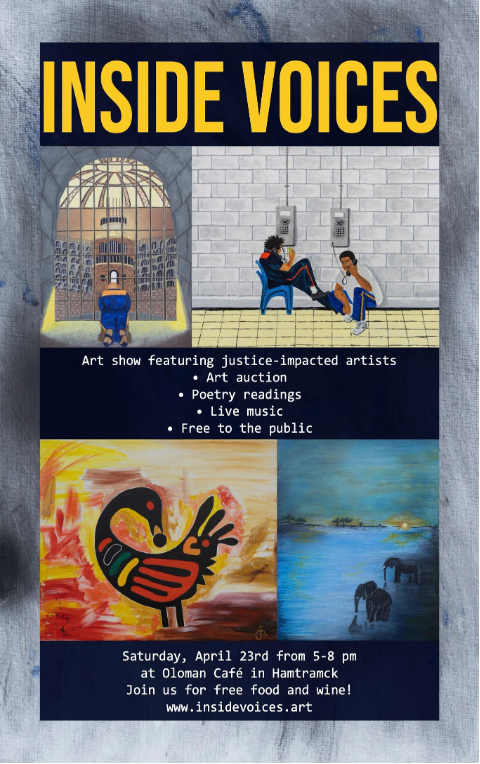

Image Credit: Zenon Sommers and Bella Martincic

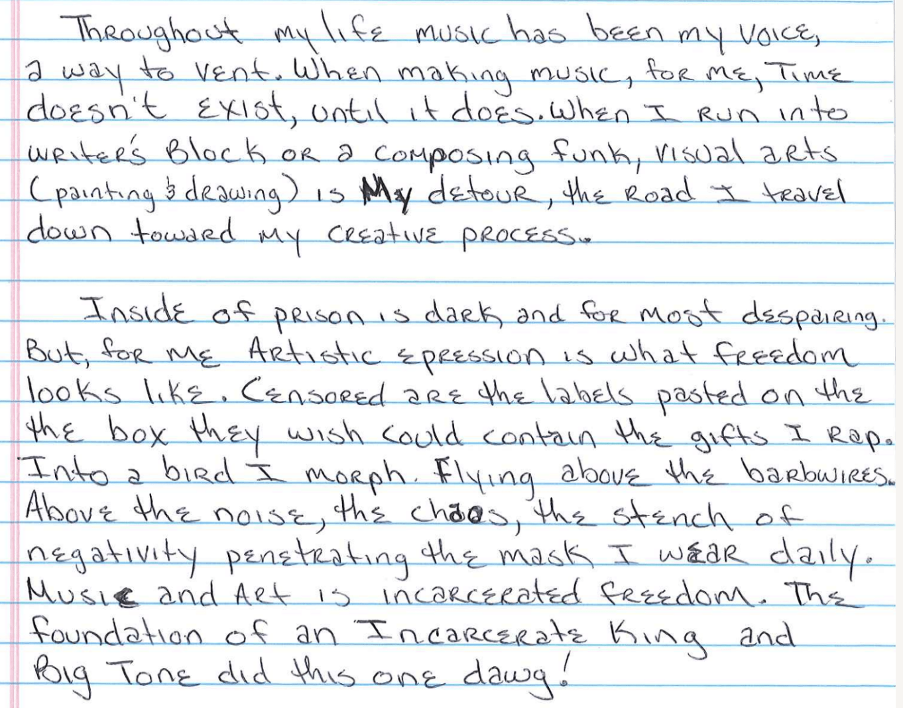

In this way, the class experience echoed a deeper truth: that even in extreme constraint, people find ways to resist, remember, and reimagine themselves and the world around them. As expressed by Big Tone, one of the still-incarcerated members of the Theory Group,

Photo Credit: Paul Draus, text by Tony Tard

The class concluded with an art exhibit at the Oloman Café and Gallery in Hamtramck, Michigan, where relatives of the incarcerated artists read their poems and their paintings were sold, with proceeds going to a local reentry advocacy organization. The university students were also asked to write “Shining Moments Haiku” that reflected their experience in the course. These highlighted the insights about incarceration as well as the sense of community developed in the course, as evident in the examples below:

Strangers become friends

As they enjoy stories told

Flowers, music, voiceCircle of laughter

Bonding those who would never

Have met otherwiseTheir stories command

You to listen and think of

The voices unheardWhat we think is true

About incarceration

Could not be more wrong

Penny Kane, one of the formerly incarcerated guest professors, described the experience powerfully: “This class has rocked my world. The students have blown me away. What you learn here, especially from people who’ve lived it, you’ll never find in a textbook.” The class encouraged students to break down stereotypes, engage deeply with lived experience, and see incarceration not as a distant issue but as a human crisis. As one student put it, quoting a guest professor, “This isn’t gravity. These systems were created—and if they were created, we can change them.”

The Art & Agency Workshops (AA): Creative Practice in the Community

There was a focused energy in that post-Covid IO class, as well as an openness and a shared sense of purpose that we were reluctant to lose once the semester ended. Inspired by this experience, we proposed a series of workshops with a similar format, but open to a broader community, and not confined to students who had registered for a semester-long class. Rather than being instructor-driven, these workshops would be led by invited artists and facilitated by formerly incarcerated individuals, creating a space where art, storytelling, and reflection could continue to foster dialogue and connection.

The AA workshops emerged as a natural next step—a way to sustain our momentum and make the transformative potential of IO available beyond the university classroom. Themes that resonated deeply in the IO course—resilience, identity, and healing—became the foundation for these workshops, which were designed to extend the dialogue and creative practice to the community. Launched in Fall 2023, with support from the University of Michigan’s Arts in the Curriculum program, the AA workshops took place twice a month at the Office of Metropolitan Impact/Ford Collaboratory on the UMD campus. They were open to students, community members, and the general public.

Each session was organized around broad and inclusive themes such as fear, joy, connection, hope, healing, innovation, resilience, and restoration. Artists from the metropolitan Detroit area were invited to lead individual workshops and follow-up debriefing sessions. They included poet Kristin Palm, painter Sabrina Nelson, playwright Shawntai Brown, storytellers Shannon Caason and Jeremy Hansen, sculptor Aaron Kinzel, photographers Khary Mason and Romaine Blanquart, dancers Joshua Bisset and Laura Quatrocchi of the Shua Group, as well as Olatz Gorrotxategi, an actress and theater director from Spain. Each session was co-facilitated by formerly incarcerated individuals—drawn from the same group that acted as guest professors in our IO course.

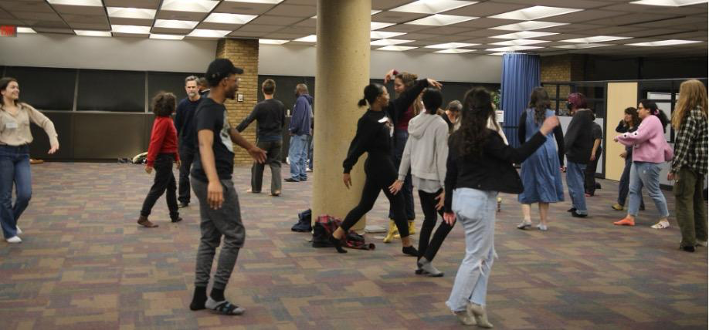

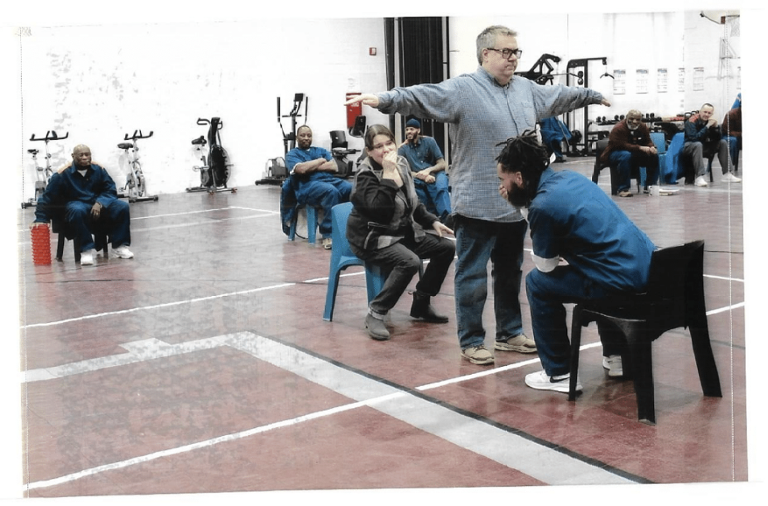

The facilitators introduced each theme by sharing reflections that wove together their prison and post-prison experiences, grounding the workshops in lived reality. For example, in poetry workshops with Kristin Palm, they emphasized the importance of writing and the concise expression of emotion; in the sessions centered on movement, with Joshua Bisset and Laura Quatrocchi, they spoke of the profound limitations placed on physical freedom in prison and invited participants to reflect on the meaning of movement in their own lives (see Figure 3). In a workshop on healing with Sabrina Nelson, the participants imagined themselves as healing herbs which we then visually represented; in a theater workshop, we used techniques from the theater of the oppressed to express emotions and share our worries, while also creating space for joy and play. All the workshops were followed by debriefing, in which participants came together to process these experiences and discuss what they had learned—both about themselves and about the social issues explored through art.

Photo credit: Anna Müller

One of the most impactful workshops was called “The Art of Conversation” led by Khary Mason and Romain Blanquart. They invited us to reflect on what it truly means to engage in conversation and the many forms dialogue can take. Before diving into photography-based exercises, Khary and Romain led us through an exercise designed to show why conversations matter. Each of us carries stereotypes—assumptions about different groups of people that can shape our views in unconscious and harmful ways. While it may be easy to accept these stereotypes, doing so can damage not only those we judge but also our own capacity for empathy and understanding. It is through intentional, open dialogue—especially with those from groups we may hold biases toward—that we begin to break down these assumptions and learn to see others as the full, complex individuals they are.

To make this tangible, the facilitators asked us to pair up with someone we did not know well and practice attentive listening by taking turns speaking for several minutes on a personal theme while the other person remained fully present–listening without interruption, questions, or judgment. Afterward, we reflected together on what shaped mutual understanding: tone of voice, body language, the patience to let silence linger, and the openness to hear another’s experience without immediately filtering it through our own assumptions. In this way, the conversation itself became a mirror for the work of seeing: just as portraits are never mere headshots but layered, emotional, and complex representations, so are people multi-dimensional, requiring time and care to be truly seen.

Each workshop created a space for building community and engaging in transformative dialogue, with creative practice approached as a humanizing process rather than an individualistic pursuit. In fact, the workshops themselves were grounded in very specific, embodied practices. Each session began with formerly incarcerated facilitators sharing a piece of their lived experience connected to the workshop’s theme—for example, the profound limitations they had faced on expressing emotions inside a prison, the meaning in small gestures such as a hug, or the restrictions placed on movement in time and space. In one workshop, we discussed the difficulty of accessing everyday products that make life manageable in incarcerated settings, noting the stark differences between men’s and women’s prisons; in another, facilitators reflected on the isolating effects of sensory deprivation. These personal accounts opened the space and framed the exercises that followed—whether poetry, photography, movement, or theater—by rooting them in lived realities of constraint and survival. From this grounding, participants could engage not as detached observers but as co-creators, reflecting on freedom, healing, and community in ways that were deeply relational and transformative. Hence, AA modeled what a more humane and inclusive society might look like—one where dignity is affirmed, listening is prioritized, and creativity becomes a shared path toward social understanding and change.

One of the students reflected on the AA workshops over a year after graduating from the University:

I loved how it was an immediate community. Every workshop was liberating in how much expression and honest conversation occurred so naturally. I feel like we don’t get to have dialogues that open and safe often. It was a bright spot in my week. My favorite workshop was probably the two-part photography workshop, where we partnered off and did portraits, and then used a disposable camera to capture our lives until the next meeting. Going through the portraits and having other people really describe how they see your essence and personality in them was touching, as well as the written messages people added. Taking snapshots of my life and having them all printed out reminded me of the simple things I found joy in.

Who’s Your Neighbor? (WYN): Extending Creative Dialogue Across Communities

With AA, we had developed an effective collaborative approach to working with students, community participants and visiting artists, maintaining a focus on the experience of incarceration or other forms of social exclusion and fostering empathy across social boundaries. We then decided to take it one step further by bringing the model into broader, more diverse community spaces. The team of formerly incarcerated individuals and Paul Draus, Anna Muller, and Kristin Palm chose the theme of “Who’s Your Neighbor?” because they felt that it allowed explorations of how social distance and othering play out in the context of daily life in the communities to which they were returning. It also had resonance with the experience of incarceration itself, as the intense physical proximity of housing units make knowledge of one’s neighbors a survival strategy.

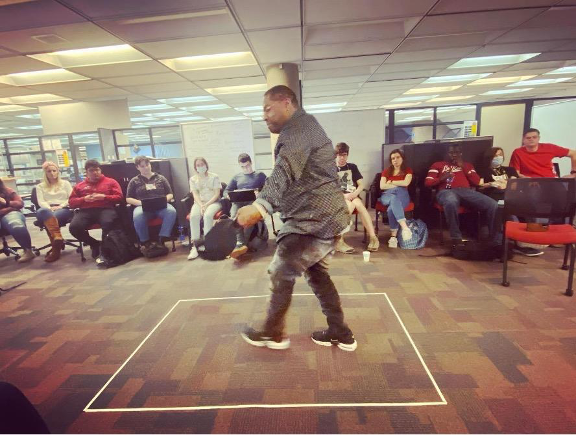

Though no longer directly focused on the experience or impact of prison, the workshops were all led by formerly incarcerated men and women (and IO alumni), joined by professional/practicing artists who shared creative practices exploring questions such as: Who are your neighbors? Why do we care? Why do we include some and exclude others? This series of six workshops took place from October 2023 to April 2024 with support from the University of Michigan’s Engage Detroit Workshop Program and the Office of Community Engaged Learning (OCEL) at UM-Dearborn. They were created in collaboration with community partners like InsideOut Literary Arts and the Youth Justice Fund.

In the WYN workshops, diverse groups of participants—university students, staff and faculty, formerly incarcerated individuals, urban and suburban youth, policymakers, members of law enforcement, artists, and other members of Detroit communities—engaged in various creative arts practices designed to spur conversation, sharing, understanding and collaboration. Under the direction of facilitators trained in various expressive arts, participants connected across boundaries, opening up, sharing and discussing problems linked to social inequality, as social inequality relates to experiences of the carceral system in the United States.

The initiative included a workshop focused on dance and movement at the Andy Art Space on the north side, a music-making workshop with Neptune XXI at the University of Michigan Detroit Center, and a storytelling/poetry workshop at the Hannan Center, a senior services organization located in Detroit’s Midtown. This last workshop, led by educator and slam poetry champion Jassmine Parks, used colored yarn as a prop to create separate “neighborhoods” amongst an audience that was diverse in terms of ethnicity, gender and age, leading participants to reflect on the way they define both difference and similarity (see Figure 4 below). In their separate groups or “neighborhoods,” participants responded to the following questions:

- Do you have good neighbors? What makes you say that?

- Do you consider yourself a good neighbor? Why or why not?

- Who would you love to move next to you?

- Have you ever argued with a neighbor?

- Have you ever shared a meal with your neighbor?

- Have your neighbor or you ever done something nice for someone in your neighborhood?

- Have you ever had or have you ever been a nosy neighbor?

Photo credit: Paul Draus

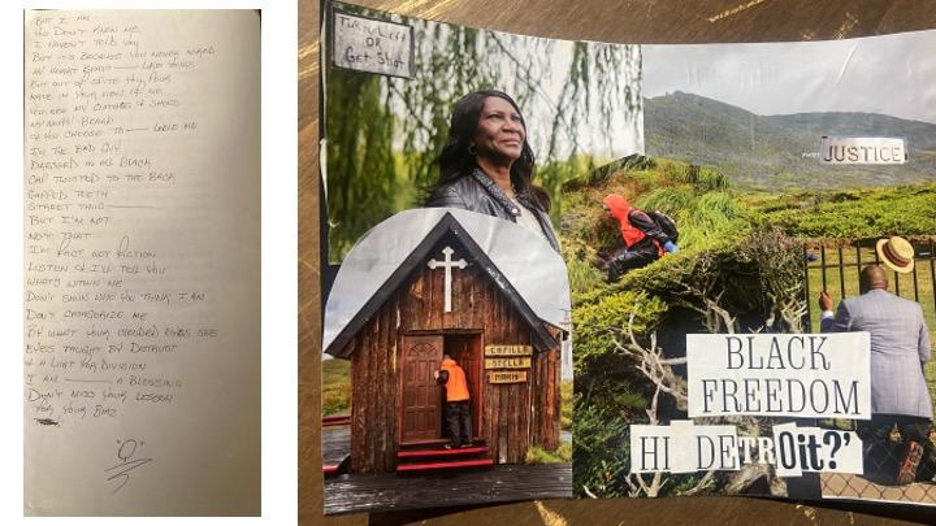

In March 2024, we organized a WYN workshop at Equity Alliance on the west side of Detroit, featuring collage artist and entrepreneur Robin M Wilson. Using examples from her own work, Wilson guided participants in using collage as a way to express individual and cultural identity and explore the idea of community. UMD student Penny Kane facilitated the workshop, which included about twenty participants from Detroit, Dearborn, and Inkster, who created their own individual collage pieces while also contributing to a group collage exploring the theme of community. Participants worked in groups at tables with collage materials provided, and individuals were invited to discuss their collages in front of the whole group. Q, a formerly incarcerated artist and TG member, showed his collage and discussed the conflicted feelings he experienced coming back to his hometown of Detroit following his release:

Photo credit: Paul Draus

The images conveyed a sense of searching, an attempt to return “home”, to a place of freedom, that also entails a community connection. The text accompanying the collage reads as follows:

But I Am

You don’t know me

I haven’t told you

But it’s because you never asked

My heart beats—like yours

But out of spit you pour

Hate in your view of me

You see my clothes & shoes

My nappy beard

And you choose to—label me

I’m the Bad Guy,

Dressed in all black

Cap twisted to the back

Gapped teeth

Street thug—-

But I’m not

Not that

I’m fact not fiction

Listen and I’ll tell you

What’s within me

Don’t shun who you think I am

Don’t categorize me

By what your clouded eyes see

Eyes taught by Detroit

& a lust for division

I am—–a blessing

Don’t miss your lesson

For your bias“Q”

As with AA, these March 2024 workshops addressed the themes of identity and belonging versus othering and division, but through the daily struggles of local individuals.

Returning Inside: Integrating New Approaches within Correctional Settings

After working to build community on the outside with the support of formerly incarcerated individuals, we decided to “close the loop” and do an AA workshop inside Macomb Correctional Facility with the remaining members of the Theory Group (TG) in February 2025. We began teaching inside the prison again in 2023, although it took additional time to resume meetings with the TG. Thankfully, several more TG members have now been released from prison, and have begun working with our AA programs on the outside. As the AA workshops with artists have informed our teaching, we have integrated more embodied creative practices into our work within the facility. We believe that movement and physical expression open up new pathways for thinking, reflecting, and engaging—approaches we are increasingly drawn to as we explore deeper possibilities for dialogue and transformation in carceral spaces.

At the International Conference on Prison Education held in Montreal, Quebec, in October 2024, we conducted an AA workshop utilizing “speed collaging” as a way to engage our audience as participants in the process of building community and sparking dialogue through creative practice. We had developed this technique with Penny, one of our guest professors, at the Inside-Out 25th anniversary conference held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in November 2023, and at a Creativity Lab workshop at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor in May 2024. In Montreal, we were also able to experience a session that was facilitated by members of the Walls to Bridges (W2B) program, a Canadian cousin of IO based in Toronto. We were so inspired and excited by their work that we began a collaborative conversation on the spot and invited Hope McIntrye, W2B instructor and Associate Professor of Theater at the University of Winnipeg, to come to Michigan and share some theater techniques with us (Unfortunately, the formerly incarcerated W2B members are not yet able to travel across the US border).

With Hope’s guidance, the TG members at Macomb Correctional Facility planned and organized a three-hour workshop for approximately thirty members of the prison population. It was an ambitious agenda that included three phases: First, they led small groups of participants through multiple theater-based exercises (first hour). The exercises included Busy Restaurant, in which participants animated a fictional space through improvised gestures and imagined interactions, exploring spatial awareness and the shared construction of the environment. In Find Your Partner, pairs reconnected through nonverbal cues (sound or motion), cultivating sensitivity, focus, and playful vulnerability. Slow Motion Race invited participants to resist urgency and inhabit time differently, emphasizing control, attention, and embodied reflection. With Tableaus, small groups used their bodies to form frozen scenes that captured abstract concepts like injustice or community, encouraging collective interpretation and symbolic thinking. The last exercise, Three-Legged Monster, challenged groups of three to become a single moving entity, navigating the room together and practicing nonverbal coordination and trust.

We then distributed unique original stories for each of the groups to read and dramatize (second hour), using theater techniques learned in the previous exercises. The stories had been developed by the members of the TG, who recorded narratives drawn from their own experiences, both prior to and since their incarcerations. One of them, “The Lion”, focused on a man who had to be a protector for his younger siblings, both at home and in the neighborhood. His proficiency for violence, born of the need to protect others, soon landed him in prison. Eventually, he became a mentor for other incarcerated young men, who he sought to protect not through violence but through education. He wrote: “You try to help them, you know, because a lot of children out there today, they don’t have no role models.” The group assigned this story figured out a way to effectively convey the idea of the man’s journey to the rest of the audience through movement and nonverbal expression.

Finally, in the third hour, participants presented these dramatized scenes to the entire group (see Figure 6). After watching each short scene, the audience was given the opportunity to enter the scene and change a key element that would then alter the outcome of the story. For example, in “The Lion”, an audience member was able to enter the scene and interrupt the violence in the neighborhood, replacing it with community care and support, giving the young man other options besides the path that led to incarceration. This was followed by a whole-group dialogue which examined the role of choice (or agency) in producing different outcomes in people’s lives, as well as in communities. Art, in this case theater, became a vehicle for representing one’s experience, for envisioning alternatives, and for transforming the world.

Photo Credit: Derrious Lambert

Discussion: Pedagogical Reflections and Theoretical Perspectives

The AA program’s full title was “Art & Agency from the Inside Out: Building Space for Critical Dialogue and Emotional Expression through Creative Practice.” Originally inspired by IO, AA explored how creative practice can illuminate inequalities in the community, while fostering internal transformation and enhancing one’s agency and ability to act in the world. As Paulo Freire stated about words expressed in true dialogue: “To exist, humanly, is to name the world, to change it… saying that word is not the privilege of some few persons, but the right of everyone” (1970, 2000, p. 88). AA likewise posited that art was not merely aesthetic but profoundly political—especially when co-created by people whose lives have been shaped by systems of confinement.

The WYN workshops extended the dynamic learning environment of AA to diverse community settings, while adding an emphasis on creative practice as a form of critical education. By this time, we had developed an effective approach to working with students, community participants, and visiting artists, maintaining a focus on the experience of incarceration or other forms of social exclusion and fostering empathy across social boundaries. Through brief immersion in various expressive arts, participants were able to engage in exercises and dialogue that helped them connect, open up, share and understand problems related to social inequality, especially as it relates to experiences of the carceral system in the United States.

A key theoretical underpinning of the AA workshops lies in their reliance on embodied and experiential knowledge, particularly as articulated by formerly incarcerated facilitators—many of them alumni of IO. These facilitators opened each session with personal narratives or participatory exercises that linked the theme of the workshop to lived experience within carceral institutions. In doing so, they reframed everyday gestures, such as touching, hugging, active listening, or interpersonal conversation as acts of resistance against a carceral regime that disciplines the body and polices intimacy. Within such constrained environments, these seemingly mundane actions acquire heightened meaning, becoming what Michel de Certeau (1984) would call “tactics” of survival and subversion—small acts that momentarily reclaim autonomy within a space structured by control.

This reframing aligns with James C. Scott’s theory of “hidden transcripts” (1990), which describes the subtle, everyday forms of resistance employed by subjugated groups under systems of domination. Scott emphasizes that such acts, including satire, prayer, emotional support, or cultural memory are not mere symbols but active strategies for maintaining selfhood, solidarity, and moral agency. In the context of the AA workshops, the facilitators’ stories and practices highlighted how creative acts such as writing, drawing, or performing may also function as counter-discourses: ways of asserting identity and humanity in spaces designed to suppress both. These expressions, while often unnoticed or undervalued by institutional authority, are sociologically significant forms of agency that defy the erasure of subjectivity. The IO program and AA/WYN workshops are also deeply informed by Paulo Freire’s critique of the “banking model” of education (1970, 2000), which positions students as passive recipients of knowledge. Instead, the three initiatives embrace Freire’s vision of dialogical pedagogy, where learning emerges through collective inquiry, mutual vulnerability, and critical reflection (Weil Davis and Roswell, 2013). In this framework, facilitators and participants co-construct knowledge, blurring the hierarchies between teacher and learner and transforming the classroom into a site of shared exploration.

Complementing Freire’s epistemology is Sherry Shapiro’s theory of embodied pedagogy (1999), which critiques the marginalization of bodily knowledge in traditional education systems. Shapiro argues that dominant pedagogies perpetuate Cartesian dualisms—mind over body, reason over emotion—which serve to uphold institutional hierarchies and suppress alternative ways of knowing. AA/WYN’s integration of movement, performance, and physical improvisation functions as a counter-practice: it reclaims the body as a site of knowing, feeling, and acting, and reaffirms the dignity of those whose embodied knowledge has been criminalized or ignored. By foregrounding these modalities, AA/WYN not only democratize the learning space but also activate a form of pedagogy that is affective, relational, and transformative.

The presence of formerly incarcerated facilitators on the outside is especially significant. Inside the prison, there is an intensity of interaction produced by the setting itself—the absence of distracting technology, the confinement within a limited space with those often presumed to be essentially “other”, and the weight of the social consequences of incarceration all around. Outside the prison, engaging as free people, bearing the burden of their experience and associated stigma in their daily lives but now serving as co-educators, they challenged assumptions about who holds knowledge and what kinds of experience count in educational settings. Workshop activities emphasized vulnerability, mutual recognition, and embodiment as pedagogical tools. In a society that often marginalizes or criminalizes certain bodies, inviting movement and physical expression into educational spaces was itself a radical act. The use of collaborative storytelling, visual art, and theatrical expression allowed participants to explore emotional landscapes and social issues in ways that were accessible, personal, and transformative—retaining the connection to incarceration but not defined by it, rather aspiring to its opposite, a community of people free to associate, create and act in the world.

Agency is best understood as situated and relational, existing in a dialectic relationship with structures of control. Even small decisions, seemingly insignificant, are acts of agency that may subtly push against the logic of oppressive systems. Erving Goffman’s (1961) concept of the total institution (e.g., asylums, prisons, camps) is central to this sociological framework. Such institutions strive to strip individuals of identity and autonomy, yet even within them, people develop coping strategies, informal roles, and subcultures. In concentration camps, for example, these might have included shared songs, mutual aid, or underground educational efforts—all forms of constrained agency that allowed individuals to assert their humanity under extreme conditions. In American prisons, these coping strategies took other forms. In one of our workshops, Lacino stood in a box on the floor that represented the size of an isolation cell to show how he still managed to persist and resist by pacing its narrow length, exercising his body, and using his imagination to create a sense of movement and freedom even within extreme confinement (see Figure 7). Seen in this light, the workshops of our initiatives themselves become a form of group agency asserted against the logics of othering that undergird oppressive systems, including (but not limited to) regimes of mass incarceration.

Photo Credit: Paul Draus

Conclusion and Future Directions

The Art & Agency/Who’s Your Neighbor? workshops—rooted in the Inside-Out model and co-facilitated by formerly incarcerated individuals and professional artists—demonstrated that meaningful dialogue and personal transformation are possible when education, creativity, and justice work intersect. Whether through poetry, movement, photography, or theater, creative practice allows participants to engage with complex social issues—mass incarceration, exclusion, healing, and community—in deeply personal and accessible ways. Art fosters empathy. From photography workshops to story circles, the act of listening emerged as essential to building mutual understanding. True dialogue begins with presence—seeing and hearing others without rushing to interpret, defend, or fix. As our recent emphasis on theater and movement-based practices shows, embodied engagement encourages different ways of knowing and being.

In terms of takeaways from the prison theater workshop, one of the incarcerated participants wrote:

I took away humanity. I felt like Saturday represented the genuine humane interaction necessary to have another shift in society. We need more of that going on, in even greater pockets of our society. I felt powerful, alive, and in awe by the abundance of sincerity that was encapsulated inside of that gymnasium.

Another man, Radu, spoke of the plays that re-enacted key turning-point events from the lives of incarcerated men and said:

The most important thing to take away from those reflections, in my opinion, is the effect our actions and our words have on other people. The ripples of our attitude, even in the most minute things, extend beyond the horizon. One seemingly insignificant act of kindness today can, and probably will, result in changing one or possibly multiple lives for the better. The same goes for an act of selfishness, a hard or abrasive word, or even a condescending look. I believe this was described as “the butterfly effect.”

While our journey may have come full circle, it is anything but over. In Radu’s words, one ripple spreads to the next. As we move forward with our intertwined IO/AA programs, we intend to reconnect more systematically with IO alumni—both inside and out—to co-develop programming, facilitate new workshops, and sustain momentum. We also plan to continue developing theater- and movement-based workshops, recognizing their power to surface emotions, build trust, and create community. This could include training facilitators in somatic pedagogies and collaborating with additional performance artists, as well as assessing the impacts of the workshops in the short and long term.

Finally, we hope to develop a flexible, living curriculum based on the IO/AA/WYN model that can be adapted for use in schools, community centers, and other carceral and post-carceral spaces. As faculty trained in the fields of History and Sociology, we find that our traditional form of scholarly output (i.e. the research article) is too restrictive and limited to capture or convey what we are doing with this project. We want to consider ways in which the diverse artists and artistic forms may be drawn together in a cohesive but multi-textual format, for example as a series of short films or a collaborative performance that counters the dynamics of dehumanization currently at play in our politics. Rather than focusing primarily on the logics of incarceration, which dehumanize people and deny their agency, we wish to effectively build the alternative: a space of human community where the capacity for creative expression defies all attempts to jail it.

Statement on Limitations

We acknowledge that we did not engage in a formal process of collecting surveys or systematic responses from participants in the AA workshops. This is a shortcoming of our current approach. Initially, we viewed the workshops as an informal extension of the Inside-Out model, focused on sustaining relationships and creative dialogue during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Only over time did we come to recognize their potential as powerful tools for community building and public pedagogy. As a result, our current findings are largely anecdotal and based on informal feedback, observations, and participant comments. Moving forward, we intend to incorporate more structured evaluation methods to better understand the workshops’ long-term impact and inform future iterations of the AA initiative.

References

- Borowski, T. (2021). Here in Our Auschwitz and Other Stories. Yale University Press.

- Boym, S. (2007). Territories of Terror: Mythologies and Memories of the Gulag in Contemporary Russian-American Art. Boston University Art Gallery.

- Darrow, C. (2000). Crime & criminals: address to the prisoners in the Cook County Jail & other writings on crime & punishment. Despres, Leon Mathis, 1908-2009.

- De Certeau, M. (1984). The Practice of Everyday Life. University of California Press.

- Draus, P. J. and Lempert, L. B. (2013). Growing Pains: Developing Collective Efficacy in the Detroit Theory Group. The Prison Journal 93(2), 139-162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885512472647

- Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Random House, Vintage Books.

- Freire, P. (1970, 2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed: 30th anniversary edition (M. Bergman Ramos, Trans.). Continuum.

- Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Doubleday.

- Hamilton, L. (2023). In Spite of the Consequences. Prison Letters on Exoneration, Abolition, and Freedom. Broadleaf Books.

- Ignatieff, M. (1978). A Just Measure of Pain. Pantheon.

- Scott, J. C. (1990). Domination and the Art of Resistance: Hidden transcripts. Yale University Press.

- Shapiro, S. (1999). Pedagogy and the Politics of the Body. Routledge.

- Thoreau, H. D. (2000). Walden; and, Civil Disobedience: Complete Texts with Introduction, Historical Contexts, Critical Essays. Houghton Mifflin.

- X, Malcolm, and Haley, A. (1989). The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Ballantine Books.

- Weil Davis, S. and Roswell, B. S. (2013). Turning Teaching Inside Out: A Pedagogy of Transformation for Community-Based Education. Palgrave McMillan.

Notes

- Abolitionist scholars argue that prisons do not solve social problems but rather reproduce structural inequalities, particularly along lines of race, gender, and class. Abolition means, then, is not simply tearing down prisons but committing to a reorganization of social life—one that addresses harm through accountability, healing, and structural change rather than through surveillance and punishment. In practice, this includes investing in restorative and transformative justice processes, community-based mental health care, affordable housing, accessible education, and other forms of collective infrastructure that reduce vulnerability and build safety without relying on incarceration. On prison abolition as both a political project and an ethical imperative, see Angela Y. Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete? (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003), which challenges the “naturalness” of carceral systems and calls for imagining alternative modes of justice beyond punishment. ↩︎

- Lacino later published a book composed of his personal letters, Lacino Hamilton, In Spite of the Consequences. Prison Letters on Exoneration, Abolition, and Freedom (Minneapolis, Broadleaf Books, 2023). See https://www.lacinohamilton.com/ Read more about Darryl Woods’ journey here: https://outliermedia.org/darryl-woods-detroit-board-police-commissioners-chair-elect/ ↩︎

Authors

Paul Draus

Professor of Sociology

University of Michigan-Dearborn

draus@umich.edu

Anna Müller

Professor of History

Social Sciences Department

University of Michigan-Dearborn

anmuller@umich.edu

Cite this article

Draus, P. and Müller, A. (2025). From Confinement to Connection: The Evolution of the Art & Agency Workshops. Apprendre + Agir, special issue 2025, Learning and Transforming: International Practices and Perspectives on Prison Education. https://icea-apprendreagir.ca/from-confinement-to-connection-the-evolution-of-the-art-agency-workshops/